Over a long weekend in early November, 1973, Jackson State College (now University), an Historically Black College and University, hosted a bicentennial celebration at its Mississippi campus of Phillis Wheatley’s 1773 Poems. The organizers, bolstered by National Endowment for the Humanities funding and army of volunteers, brought together leading scholars of the eighteenth-century poet as well as leading voices from the then-burgeoning literary Black Arts Movement. The four-day “Phillis Wheatley Poetry Festival” garnered considerable media support, including local and regional television, a photographer from the New York Times, and a glowing write-up in Black World magazine–see Carole A. Parks, “Report on a Poetry Festival: Phillis Wheatley Comes Home” (1974). The Jackson State Review also devoted an entire issue to the Festival, capturing the extraordinary ferment and the significance of Wheatley at that specific moment. The issue’s frontispiece displays a bust of the poet, by noted sculptor Elizabeth Catlett, revealed that weekend); a ten-page roster of supporters and volunteers; transcriptions and facsimiles of archival documents; selected scholarly articles, a bibliography, authors bios, and a copy of the program. If I owned a time machine and could attend any one single academic conference from the last century, it would be this gathering–the Monday, November 5 morning session combined music (including a recital of James Weldon Johnson’s “Lift Every Voice and Sing”), readings by poets Audre Lorde, Lucille Clifton and June Jordan, and Alice Walker sharing her now-landmark tribute, “In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens” (1974).

Over a long weekend in early November, 1973, Jackson State College (now University), an Historically Black College and University, hosted a bicentennial celebration at its Mississippi campus of Phillis Wheatley’s 1773 Poems. The organizers, bolstered by National Endowment for the Humanities funding and army of volunteers, brought together leading scholars of the eighteenth-century poet as well as leading voices from the then-burgeoning literary Black Arts Movement. The four-day “Phillis Wheatley Poetry Festival” garnered considerable media support, including local and regional television, a photographer from the New York Times, and a glowing write-up in Black World magazine–see Carole A. Parks, “Report on a Poetry Festival: Phillis Wheatley Comes Home” (1974). The Jackson State Review also devoted an entire issue to the Festival, capturing the extraordinary ferment and the significance of Wheatley at that specific moment. The issue’s frontispiece displays a bust of the poet, by noted sculptor Elizabeth Catlett, revealed that weekend); a ten-page roster of supporters and volunteers; transcriptions and facsimiles of archival documents; selected scholarly articles, a bibliography, authors bios, and a copy of the program. If I owned a time machine and could attend any one single academic conference from the last century, it would be this gathering–the Monday, November 5 morning session combined music (including a recital of James Weldon Johnson’s “Lift Every Voice and Sing”), readings by poets Audre Lorde, Lucille Clifton and June Jordan, and Alice Walker sharing her now-landmark tribute, “In Search of Our Mother’s Gardens” (1974).

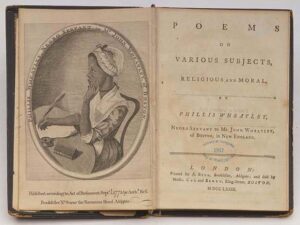

The criticism on Phillis Wheatley has always carried this broader legacy, on the status of black arts in the United States. Textual scholarship for this reason is particularly important: revision and the composition process, including variants, hint to what she could or could not write. The first edition of Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773) included an endorsement by her captor John Wheatley, and a notice “To the Publick,” signed by civic lights, testifying to the volume’s authenticity. The book was reviewed and reproduced widely, often alongside anti-slavery efforts, notably the 1834 Memoir and Poems of Phillis Wheatley, with a widely-cited remembrance by Margaretta Matilda Odell; the Odell volume is readily accessible through the University of North Carolina Library’s DocSouth project. Modern editions play a kind of textual hopscotch, marking the interplay between black and white assessments of Wheatley. Julian D. Mason, Jr., The Poems of Phillis Wheatley (1966) emphasizes historical contexts, with a publication date corresponding to the Civil Rights Movement. A facsimile edition, prepared by a leading scholar William H. Robinson for Garland Press’ “Critical Studies in Black Life and Culture” series (edited by Henry Louis Gates, Jr.), includes a long critical essay, and recovers several key documents; Robinson notably takes pains to distance the text from editorial intrusion, presents Wheatley’s words in the most literal form. Mason published a revised edition in 1989, duplicating or providing more complete versions of texts that had come to light. John C. Shields edited The Collected Works of Phillis Wheatley (1989), as part of the Schomburg Library of Nineteenth-Century Black Women Writers, a project also overseen by Gates. From this thicket of texts, I prefer for teaching purposes the Penguin Complete Writings (2001), edited by Vincent Carretta, which includes extant documents as well as variants, although with less scholarly apparatus.

It is an academic cliché to remark that a book could be written about the criticism, although one has been written about Wheatley studies, William H. Robinson’s Phillis Wheatley: A Bio-Bibliography (1981). John C. Shields, one of her most thorough students, offers an even-handed overview, starting from the premise that any critical assessment of Wheatley as a poet must sift through the reception history, in Phillis Wheatley’s Poetics of Liberation (2008). Early promotions and reviews discussed Wheatley’s publication within debates on racial justice. Thomas Jefferson famously derided the verse of a “Phyllis Whately” in a pro-slavery discussion of Notes on the State of Virginia (1781). Jefferson’s caricature was repeated, and challenged through the eighteenth- and nineteenth-centuries; for recaps of the literature, see the introductory essays “On Phillis Wheatley in her Boston” in Robinson (Phillis Wheatley and Her Writings) and “On the Reputation of Phillis Wheatley, Poet” in Mason (1989).

Even in highly sympathetic readings, such as Walker’s, Wheatley often seems to matter less for her verse as for her symbolic value. Commentators through the twentieth century have addressed Wheatley more as phenomenon than poet. Authors and critics of the Harlem Renaissance and after cited her mostly as a the start of a tradition that flowers later. James Weldon Johnson devotes twelve pages to Wheatley in the “Preface” of The Book of American Negro Poetry (1922), yet in a puzzling omission, leaves her out of the anthology’s contents. J. Saunders Redding, in To Make A Poet Black (1939), regards Wheatley as a tepid product of her time, valuing her “firstness.” Cold to the norms of eighteenth-century verse, critics often read Wheatley against an aesthetic that was not of her time. Vernon Loggins laments the lack of an individual voice, noting a derivative quality of the poet who read Alexander Pope instead of Wordsworth; see The Negro Author: His Development in America to 1900 (1931). An exception to this trend, which anticipates later revisionist readings, is Arthur C. Davis, whose “Personal Elements in the Poetry of Phillis Wheatley” (1953) directs our attention to Wheatley’s strategic uses of Christianity. Even after such insightful studies, nonetheless, Benjamin Griffith Brawley would settle for literature as a marker of individual poet’s character in Early Negro American Writers (1970), and Alice Walker would point to the start of an absent literary tradition.

Criticism turned a corner following the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s-70s, and the resulting theorization. Robert Hayden’s “A Letter from Phillis Wheatley: London 1773” (1970, 1984) splices a letter Obour Tanner with contemporary interpolations, and the 1973 Jackson State conference galvanized a “who’s who” of contemporary black women poets around her legacy. On the scholarly front, Merle A. Richmond (one of few critics to note the significance of Wheatley’s 1838 reprinting) would use biography to foreground lost black African identity, and negotiations between black and white worlds, in his 1974 Bid the Vassal Soar: Interpretative Essays on the Life and Poetry of Phillis Wheatley (ca. 1753-1784) and George Moses Horton (ca. 1797-1883). Anne Applegate offers a brief but early appreciation, noting Wheatley’s importance within a black tradition while stopping with an apologia of derivative style, in “Phillis Wheatley: Her Critics and Her Contribution” (1975). Terence Collins, in “Phillis Wheatley: The Dark Side of the Poetry” (1975), sees an internalized racism in the poems for African-Americans to avoid. Nigerian critic Chikwenye Okonjo Oguyemi finds traces of blackness behind the neo-classical conventions in “Phillis Wheatley: The Modest Beginning” (1976), while Mukhtar Ali Isani sees in the mature verse especially an artful use of the motif of Africa; see “‘Gambia on My Soul’: African and the African in the Writings of Phillis Wheatley” (1979). S.E. Ogude, the first to cluster individual poems into groups (rather than reading one lump), presents limited artistic successes within the context of her time; see his long chapter in Genius in Bondage: A Study of the Origins of African Literature in English (1983). June Jordan’s “The Difficult Miracle of Black Poetry in America; Or, something Like a Sonnet for Phillis Wheatley” (1986), being a model of creative writing “craft criticism,” revisits the life to expose the gaps between black experience and (white) poetic expression. For a later assessment of the critical tradition, with attention to the Black Arts Movement, see Marsha Watson “A Classic Case: Phillis Wheatley and Her Poetry” (1996).

Wheatley criticism intersects with feminism, critical race studies, and the debate over whether separate spheres should exist. Houston A. Baker, Jr. reads Wheatley from the frontispiece of her Poems, seeking an African voice released from rhymed couplets in The Journey Back: Issues in Black Literature and Criticism (1980). Henry Louis Gates, Jr. returns to the preferatory endorsement in “Writing ‘Race’ and the Difference It Makes” (1985), using her as a case in point to frame broader questions of literacy and race. Baker and Gates set the terms through most of the decade. Rafia Zafar positions Wheatley as both American and African-American in We Wear the Mask: African American Write American Literature, 1760-1870 (1997). Nellie McKay picks up the same thread, speculating on how black authorship mirrors the condition of black academics in a white university, to beg the question: “Naming the Problem That Led to the Question ‘Who Shall Teach African-American Literature?’; or Are We Ready to Disband the Wheatley Court?” (1998). Challenging Gates directly, Joanna Brooks challenges the historical pinions of the “trial,” noting how the focus on over women’s circles of patronage has led to the dismissal of Wheatley’s sentimental elegies in “Our Phillis, Ourselves” (2010). Tellingly, Brooks’ intrepid argument closes with a return to feminism in 1973–not to the gathering of women poets in Mississippi, but to the Boston publication of the white feminist sourcebook, Our Bodies, Ourselves (1970).

Pitched more broadly to postcolonial keywords of power, literary silences and marginalization, criticism exploded in the 1990s. Helen M. Burke uses Wheatley as exemplum for recovery of marginal subjects in “The Rhetoric and Politics of Marginality: The Subject of Phillis Wheatley” (1991); Burke also uses Wheatley’s vexed recourse to poetic tradition in order frame broad questions of pluralism in “Problematizing American Dissent: The Subject of Phillis Wheatley” (1994). Frances Smith Foster argues for an actualized Wheatley, who claims a literary niche for herself against the bigotry of the time, in Written by Herself: Literary Production by African-American Women, 1746-1892 (1993). Robert Kendrick argues that Wheatley challenges Enlightenment readers to examine the limits of their own narratives of subjecthood, in “Other Questions: Phillis Wheatley and the Ethics of Interpretation” (1998). Drawing from performance studies, Gay Gibson Cima argues that Wheatley rendered blackness visible to enact political change in “Black and Unmarked: Phillis Wheatley, Mercy Otis Warren, and the Limits of Strategic Anonymity” (2000). Michelle Collins-Sibley emphasizes authorial flexibility, downplaying concern for recovering an “authentic” voice, in “Who Can Speak? Authority and Authenticity in Olaudah Equiano and Phillis Wheatley” (2004). Elizabeth J. West makes a nuanced case for African traces in Wheatley’s Christianity, suggesting a poet who was neither African nor European, but who found through the Great Awakening a point of transit; see “Making The Awakening Hers: Phillis Wheatley and the Transposition of African Spirituality to Christian Religiosity” (2007). Katy L. Chiles examines non-white colonial authors and the social construction of race in “Becoming Colored in Occum and Wheatley’s Early America” (2008). Adélékè Adéèkó argues for Christianity mobilized as rhetorical resistance in “Writing Africa under the Shadows of Slavery: Quague, Wheatley, and Crowther” (2009). Vincent Carretta’s exhaustively researched biography, Phillis Wheatley: Biography of a Genius in Bondage (2011), adheres to the written archive, avoiding “speculation” and presenting a more kindly Wheatley family, who brought the poet into a transatlantic network.

Criticism that was once dismissive must now negotiate between historical readings (embedded in eighteenth-century studies) and meaningful recovery. Early Americanists and transatlanticist scholars have performed the valuable service of situating Wheatley’s poetic strategies within their era. Charles Akers sets the rhetorical goals against whiggish anti-slavery movements in Boston in “‘Our Modern Egyptians'”: Phillis Wheatley and the Whig Campaign against Slavery in Revolutionary Boston” (1973). Mukhtar Ali Isani fleshes out the imperial context in “The British Reception of Wheatley’s Poems on Various Subjects” (1981). Foregrounding biblical references in an influential essay, Sondra O’Neale shows how Wheatley used religion to dispel colonial prejudice in “A Slave’s Subtle War: Phillis Wheatley’s Use of Biblical Myth and Symbol” (1982); Samuel J. Rogal, in “Phillis Wheatley’s Methodist Connections” (1987), notes the publication of four poems (including the ode to Scipio Moorhead) in Wesley’s Arminian Magazine. Carolivinia Herron provides insight into the British epic mode in “Milton and Afro-American Literature” (1987). David Grimstead maps racial-political debates, in an essay that is long in contextualization but short on the critical tradition; see “Anglo-American Racism and Phillis Wheatley’s Sable Veil” (1989). James A. Levernier charts the relation of poems to Boston’s religious community in “Phillis Wheatley and the New England Clergy” (1991). Walt Nott draws our attention to the construction of a public persona, “From ‘uncultivated barbarian’ to ‘poetical genius’: The Public Presence of Phillis Wheatley” (1993), while Hilene Flanzbaum focuses on invocations in “Unprecedented Liberties: Re-reading Phillis Wheatley” (1993). Kirstin Wilcox subtly links the politics of the literary marketplace to poetic voice in “The Body into Print: Marketing Phillis Wheatley” (1999). In “On Her Own Footing: Phillis Wheatley on Freedom” (2001), Frank Shuffelton argues with nuance how Wheatley before the war negotiated the slippage between imperial-revolutionary discourse–and with poignancy how a post-war Boston could not sustain a free black poetics. Peter Coviello situates language of feelings within the language of the early republic in “Agonizing Affection: Affect and Nation In Early America” (2002). Astrid Franke foregrounds conventions and stock emotion in “Phillis Wheatley, Melancholy Muse” (2004). David Waldstreicher, who inexplicably lines up critical against historicist readings, recovers the micropolitics in “The Wheatleyan Moment” (2011). Christopher Cameron maps out the local political-spiritual ferment in “The Puritan Origins of Black Abolitionism in Massachusetts” (2011). Jeffrey Bilbro reflects scholarship’s transnational turn with Wheatley’s appeals to the evangelical community, in “Who Are Lost and How They’re Found: Redemption and Theodicy in Wheatley, Newton, and Cowper” (2012). Tara Bynum, one of the few to look at letters, charts the emotional language of theology in “Phillis Wheatley on Friendship” (2014). Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw offers a clear-eyed reading of the frontispiece, long attributed to Scipio Moorhead, in a recovery of a transatlantic visual rhetoric, from Portraits of a People: Picturing African Americans in the Nineteenth Century (2016).

Phillis Wheatley, in the Tremé neighborhood of New Orleans.

Wheatley criticism has matured, in short, as historicist aims have tuned themselves to postcolonial expediencies. This turn even started with close reading, as philological-archival research broadened to include social contexts. Levernier offers an early, classroom-ready exegesis of Wheatley’s signature poem in “Of Being Brought from Africa to America” (1981), and Paula Bennett, one of few critics to address Wheatley’s ode to Scipio Moorhead, presents the poetry as a space in-between in “Phillis Wheatley’s Vocation and the Paradox of the ‘Afric Muse'” (1988). Betsy Erkkila’s influential “Phillis Wheatley and The Black American Revolution” (1993) argues that the rhetoric of Revolution allowed a black African to speak doubly. That same year, 1993, a special issue of the journal Style edited by John C. Shields, would offer a consensus on technique as resistance: see Levernier, “Style as Protest in the Poetry of Phillis Wheatley”; Philip M. Richards, “Phillis Wheatley, Americanization, the Sublime, and the Romance of America”; Robert L. Kendrick, “Snatching a Laurel, Wearing a Mask: Phillis Wheatley’s Literary Nationalism and the Problems of Style”; and Shields, “Phillis Wheatley’s Subversion of Classical Stylistics.” Dwight A. McBride situates the use of Christianity within the semantic possibilities, or “discursive terrain,” of abolitionist thought in Impossible Witnesses: Truth, Abolitionism, and Slave Testimony (2001); Mary McAleer Balkun, similarly, attends to Wheatley’s negotiation of white readership in “Phillis Wheatley’s Construction of Otherness and the Rhetoric of Performed Identity” (2002). Eric Slauter turns to Wheatley to show how writers engaged contradictions between the Revolutionary rhetoric of freedom and freedom of slave in The State as a Work of Art: The Cultural Origins of the Constitution (2009). Synthesizing scholarly and creative responses, Honorée Fanonne Jeffers’ poetic project, “The Age of Phillis” (poetic essay, 2010; book, 2020) explores the “courageous artistry” that the best research into Phillis Wheatley exemplifies. The most compelling engagements with Wheatley fuse scholarship with social-political engagement, setting the poet deeply in her time while recognizing the complexities of her.

Works Cited

__________ . “Special Issue: The Phillis Wheatley Poetry Festival, November 4-7, 1973.” Jackson State Review 6, no. 1 (1974): 1-107.

Adéèkó, Adélékè. “Writing Africa under the Shadows of Slavery: Quague, Wheatley, and Crowther.” Research in African Literature 40, no. 4 (Winter 2009): 1-24.

Akers, Charles. “‘Our Modern Egyptians’: Phillis Wheatley and the Whig Campaign against Slavery in Revolutionary Boston.” Journal of Negro History 60, no. 3 (July 1975): 397-410.

Applegate, Anne. “Phillis Wheatley: Her Critics and Her Contribution.” Negro American Literature Forum 9, no. 4 (1975): 123-126.

Baker, Houston A., Jr. The Journey Back: Issues in Black Literature and Criticism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1980.

Balkun, Mary McAleer. “Phillis Wheatley’s Construction of Otherness and the Rhetoric of Performed Ideology.” African American Review 36, no. 1 (2002): 121-135.

Bennett, Paula. “Phillis Wheatley’s Vocation and the Paradox of the ‘Afric Muse’.” PMLA: Publications of the Modern Language Association of America 113, no. 1 (1998): 64-76.

Bilbro, Jeffrey. “Who Are Lost and How They’re Found: Redemption and Theodicy in Wheatley, Newton, and Cowper.” Early American Literature 47, no. 3 (2012): 561-89.

Boston Women’s Health Book Collective. Our Bodies, Our Selves. Boston: New England Free Press, 1970.

Brawley, Benjamin Griffith. Early Negro American Writers. New York: Dover Publications, 1970.

Brooks, Joanna. “Our Phillis, Ourselves.” American Literature 82, no. 1 (March 2010): 1-28.

Burke, Helen. “Problematizing American Dissent: The Subject of Phillis Wheatley.” In Cohesion and Dissent in America, edited by Carol Calatrella and Joseph Alkana, 193-209. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1994.

__________ . “The Rhetoric And Politics Of Marginality: The Subject Of Phillis Wheatley.” Tulsa Studies In Women’s Literature 10, no. 1 (1991): 31-45.

Bynum, Tara. “Phillis Wheatley on Friendship.” Legacy: A Journal of American Women Writers 31, no. 1 (2014): 42-51.

Cameron, Christopher. “The Puritan Origins of Black Abolitionism in Massachusetts.” Historical Journal of Massachusetts 39, nos. 1-2 (Summer 2011): 78-108.

Carretta, Vincent. Phillis Wheatley: Biography of a Genius in Bondage. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2011.

__________ . “Phillis Wheatley, The Mansfield Decision of 1772, and the Choice of Identity.” In Early America Re-Explored: New Readings in Colonial, Early National, and Antebellum Culture, edited by Klaus H. Schmidt and Fritz Fleischmann, 201-223. Frankfurt, Germany: Peter Lang, 2000.

Chiles, Katy L. “Becoming Colored In Occom And Wheatley’s Early America.” PMLA: Publications Of The Modern Language Association Of America 123, no. 5 (2008): 1398-1417

Cima, Gay Gibson. “Black and Unmarked: Phillis Wheatley, Mercy Otis Warren, and the Limits of Strategic Anonymity.” Theatre Journal 52, no. 4 (Dec. 2000): 465-95.

Collins, Terence. “Phillis Wheatley: The Dark Side of the Poetry.” Phylon: The Atlanta University Review Of Race And Culture 36, no. 1 (1975): 78-88.

Collins-Sibley, G. Michelle. “Who Can Speak? Authority and Authenticity In Olaudah Equiano and Phillis Wheatley.” Journal of Colonialism and Colonial History 5, no. 3 (Winter: 2004).

Coviello, Peter. “Agonizing Affection: Affect and Nation in Early America.” Early American Literature 37, no. 3 (2002): 439-468.

Davis, Arthur P. “Personal Elements in the Poetry of Phillis Wheatley.” Phylon: The Atlanta University Review of Race and Culture 14, no. 2 (1953): 191-198.

Erkkila, Betsy. “Phillis Wheatley and The Black American Revolution.” In A Mixed Race: Ethnicity in Early America, edited by Frank Shuffelton, 225-40. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993. Reprinted in Feminist Interventions in Early American Studies, edited by Mary C. Carruth. 161-182. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2006.

_________ . “Revolutionary Women.” Tulsa Studies in Women’s Literature 6 (1987): 189-223

Flanzbaum, Hilene. “Unprecedented Liberties: Re-Reading Phillis Wheatley.” MELUS 18, no. 3 (Autumn 1993): 71-81.

__________ . Written by Herself: Literary Production by African American Women, 1746-1892. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993.

Franke, Astrid. “Phillis Wheatley, Melancholy Muse.” New England Quarterly: A Historical Review of New England Life and Letters 77, no. 2 (2004): 224-251.

Gates, Henry Louis Jr. “Phillis Wheatley On Trial: In 1772, A Slave Girl Had To Prove She Was A Poet. She’s Had To Do So Ever Since.” New Yorker 78, no. 43 (2003): 82-87. Accessed Oct. 22, 2020.

__________ . “Writing ‘Race’ and the Difference It Makes.” Critical Inquiry 12, no. 1 (Autumn 1985): 1-20.

Giddings, Paula. “Critical Evaluation Of Phillis Wheatley.” Jackson State Review 6, no. 1 (1974): 74-81.

Grimstead, David. “Anglo-American Racism and Phillis Wheatley’s `Sable Veil,’ `Length’ned Chain,’ and `Knitted Heart.”‘ In Women in the Age of the American Revolution, edited by Ronald Hoffman and Peter J. Albert, 338-444. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1989.

Hayden, Robert. Collected Poems. Edited by Frederick Glaysher. New York: Liveright, 1984.

Herron, Carolivinia. “Milton and Afro-American Literature.” Re-membering Milton: Essays on the Texts and Traditions, edited by Mary Nyquist and Margaret W. Ferguson. New York: Methuen, 1987.

Isani, Mukhtar Ali. “The British Reception of Wheatley’s Poems on Various Subjects.” Journal of Negro History 66, no. 2 (Summer 1981): 144-49.

_________ . “‘Gambia on My Soul’: Africa and the African in the Writings of Phillis Wheatley.” MELUS 6, no. 1 (1979): 64-72.

Jeffers, Honorée Fanonne. “The Age of Phillis.” Common-place 11, no. 1 (Oct. 2010). Accessed Oct. 22, 2020.

___________ . The Age of Phillis. Middletown, Ct.: Wesleyan University Press, 2020.

Johnson, James Weldon, ed. The Book of American Negro Poetry. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1922.

Jordan, June. “The Difficult Miracle Of Black Poetry In America; Or, Something Like A Sonnet For Phillis Wheatley.” Massachusetts Review: A Quarterly Of Literature, The Arts And Public Affairs 27, no. 2 (1986): 252-262.

Kendrick, Robert L. “Other Questions: Phillis Wheatley and The Ethics of Interpretation.” Cultural Critique 38 (Winter 1997-98): 39-64.

__________ . “Snatching a Laurel, Wearing a Mask: Phillis Wheatley’s Literary Nationalism and the Problem of Style.” Style 27, no. 2 (Summer 1993): 222-251.

Levernier, James A. “Phillis Wheatley and the New England Clergy.” Early American Literature 26, no. 1 (1991): 21-38.

___________ . “Style As Protest in the Poetry of Phillis Wheatley.” Style 27, no. 2 (Summer 1993): 172-193.

Loggins, Vernon. The Negro Author: His Development in America to 1900. New York: Columbia University Press, 1931.

Mays, Benjamin. The Negro’s God, as Reflected in His Literature. New York: Russell and Russell, 1968.

McBride, Dwight A. Impossible Witnesses: Truth, Abolitionism, and Slave Testimony. New York: New York University Press, 2001.

McKay, Nellie. “Naming the Problem That Led to the Question ‘Who Shall Teach African-American Literature?’; or Are We Ready to Disband the Wheatley Court?” PMLA 113, no. 3 (May 1998): 359-69.

Nott, Walt. “From ‘Uncultivated Barbarian’ to ‘Poetical Genius’: The Public Presence of Phillis Wheatley.” MELUS 18, no. 3 (Fall 1993): 20-32.

Odell, Margaretta Matilda. Memoir. In Memoir and Poems of Phillis Wheatley. Boston: Light, 1834.

Ogude, S.E. Genius in Bondage: A Study of the Origins of African Literature in English. Ife-Ife, Nigeria: University of Ife Press, 1983.

Ogunyemi, Chikwenye Okonjo. “Phillis Wheatley: The Modest Beginning.” Studies in Black Literature 7, no. 3 (Autumn 1976): 16-19.

O’Neale, Sondra. “A Slave’s Subtle War: Phyllis Wheatley’s Use Of Biblical Myth And Symbol.” Early American Literature 21, no. 2 (Fall 1986): 144-165.

Parks, Carole A. “Report on a Poetry Festival: Phillis Wheatley Comes Home.” Black World 23, no. 4 (February 1974): 92-97.

Redding, J. Saunders. To Make A Poet Black [1939]. College Park, Md.: McGrath Publishing, 1968.

Richards, Phillip M. “Phillis Wheatley, Americanization, the Sublime, and the Romance of America.” Style 27, no. 2 (Summer 1993): 194-221.

Richmond, Merle A. Bid the Vassal Soar: Interpretive Essays on the Life and Poetry of Phillis Wheatley and George Moses Horton. Washington, D.C.: Howard University Press, 1974.

Roberts, Wendy Raphael. “Phillis Wheatley’s Sarah Moorhead: An Initial Inquiry.” Papers Of The Bibliographical Society of America 107:3 (2013): 345-354.

Robinson, William H. Phillis Wheatley and Her Writings. New York: Garland, 1984. Phillis Wheatley in the Black American Beginnings. Detroit: Broadside, 1975.

___________ . Phillis Wheatley: A Bio-Bibliography. Boston: G.K. Hall, 1988.

Robinson, William H., ed. Critical Essays on Phillis Wheatley. Boston: G.K. Hall, 1982.

Rogal, Samuel J. “Phillis Wheatley’s Methodist Connection.” Black American Literature Forum 21, nos. 1-2 (1987): 85-95.

Shaw, Gwendolyn DuBois. Portraits of a People: Picturing African Americans in the Nineteenth Century. Andover, Ma.: Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2006.

Shields, John C. “Phillis Wheatley’s Subversion of Classical Stylistics.” Style 27, no. 2 (Summer 1993): 252-70.

__________ . New Essays on Phillis Wheatley. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2011.

Shields, John C (ed). Phillis Wheatley’s Poetics of Liberation: Backgrounds and Contexts. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 2008.

Shuffelton, Frank. “On Her Own Footing: Phillis Wheatley on Freedom.” In Genius in Bondage: Literature of the Early Black Atlantic, edited by Vincent Carretta and Philip Gould, 175-189. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2001. 175-189.

Slauter, Eric. The State as a Work of Art: The Cultural Origins of the Constitution. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Waldstreicher, David. “The Wheatleyan Moment.” Early American Studies 9, no. 3 (Fall 2011): 522-51.

Walker, Alice. “In Search Of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Honoring the Creativity of The Black Woman.” Jackson State Review 6, no. 1 (1974): 44-53.

Watson, Marsha. “A Classic Case: Phillis Wheatley and Her Poetry.” Early American Literature 31, no. 2 (1996): 103-132.

West, Elizabeth J. “Making The Awakening Hers: Phillis Wheatley and the Transposition of African Spirituality to Christian Religiosity.” In Cultural Sites of Critical Insight: Philosophy, Aesthetics, and African American and Native American Women’s Writings, edited by Angela L. Cotten and Christa Davis Acampora, 47-65. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2007.

Wheatley, Phillis. The Collected Works of Phillis Wheatley. Edited by John C. Shields. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

__________ . Complete Writings. Edited by Vincent Carretta. New York: Penguin, 2001.

__________ . Memoir and Poems of Phillis Wheatley, a Native African and a Slave. Dedicated to the Friends of the Africans. Boston: George W. Light, 1834. Accessed Oct. 22, 2020.

__________ . Phillis Wheatley and Her Writings. Edited by William H. Robinson New York: Garland, 1984.

__________ . The Poems of Phillis Wheatley. Edited by Julian D. Mason. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989.

__________ . Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral. Boston, 1773.

Wigginton, Caroline. “A Chain of Misattribution: Phillis Wheatley, Mary Whateley, And ‘An Elegy On Leaving’.” Early American Literature 47, no. 3 (2012): 679-684.

Wilcox, Kirstin. “The Body into Print: Marketing Phillis Wheatley.” American Literature 71, no. 1 (1999): 1-29.

Zafar, Rafia. We Wear the Mask: African Americans Write American Literature, 1760-1870. New York: Columbia University Press, 1997.