I f you were a young scholar of American Literature back in the 1990s, most likely, you were a new historicist. To be a “new” historicist, as opposed to the old ones (with their sclerotic ideas about bibliography and history of thought) meant that you (the scholar) picked some quirky or forgotten nugget from the far-off past. Once you had explored the contours of this obscure factoid, reveling in its oddities, you would blow up its importance, then apply the cultural phenomenon to a bevy of literary texts–some obscure, others made new (of course) through your pathbreaking, new historicist interpretation.

f you were a young scholar of American Literature back in the 1990s, most likely, you were a new historicist. To be a “new” historicist, as opposed to the old ones (with their sclerotic ideas about bibliography and history of thought) meant that you (the scholar) picked some quirky or forgotten nugget from the far-off past. Once you had explored the contours of this obscure factoid, reveling in its oddities, you would blow up its importance, then apply the cultural phenomenon to a bevy of literary texts–some obscure, others made new (of course) through your pathbreaking, new historicist interpretation.

And that’s how I stumbled onto the Northwest Ordinance.

The Ohio Ordinances of the 1780s, culminating with the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, were the mechanism through which the United States elbowed its way onto the trans-Appalachian West, an area formerly claimed by England, running from the new states’ western boundaries to the Mississippi River.

The Northwest Ordinance set a legislative function for governing, zoing, and selling off these distant lands, bringing geographic space (and much needed revenue) into the union. It was an effective, if faceless apparatus of colonization.

If you’ve never heard of the Northwest Ordinance, don’t feel bad. In our caricatured readings of history and politics, we underestimate the power of bureaucratic machinery. We typically boil down what we see as most insidious to a single person–Adolph Hitler, Andrew Jackson, Donald Trump–and conflate government inertia with a single personality. Or we imagine “The Room Where It Happens,” the catchy dig from Hamilton where high-profile players hustle out a deal. These larger-than-life stories crowd from view more tedious processes, the butt-numbing deliberations over tiny details, the procedural checks, the drafts working up and down the corridors of power. The “room where it happens” is a boring place.

Only the real history geeks, or loyal Midwesterners, know about the Northwest Ordinance, which is not to undersell the importance of this 1787 legislation. It remains an essential, though faceless chapter in our nation’s history–which is precisely why it suited my needs as a budding new historicist. I stumbled upon a brief mention in Robert Middlekauff’s classic survey of the American Revolution, The Glorious Cause. There I learned about the first federal settlement in Marietta, Ohio. Thomas Jefferson had a hand in the first Ordinance, and the Connecticut-based Ohio Company (it turns out) included a short essay by Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur. I had my new historicist factoid! Starting from this now-obscure packet of policy, I spun out a reading of environmental-frontier literature from the early republic into a dissertation that also became my first book, From the Fallen Tree: Frontier Narratives, Environmental Politics and the Roots of a National Pastoral.

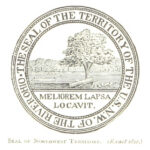

The title, From the Fallen Tree, took its cue from the official seal of the Northwest Territory, which pictured a fallen tree below the Latin phrase meliorem lapsa locavit— a better one has taken its place. How did an unwavering belief in “improvement” shape environmental writing at the time? Who were the people whose “place” had been taken? Maybe environmental writing is not such as innocent thing; as D.H. Lawrence famously wrote, “there is menace in the landscape.”

The title, From the Fallen Tree, took its cue from the official seal of the Northwest Territory, which pictured a fallen tree below the Latin phrase meliorem lapsa locavit— a better one has taken its place. How did an unwavering belief in “improvement” shape environmental writing at the time? Who were the people whose “place” had been taken? Maybe environmental writing is not such as innocent thing; as D.H. Lawrence famously wrote, “there is menace in the landscape.”

Fast forward three decades, the new historicism has fallen out of fashion. It has been supplanted by other critical movements–a new formalism, third wave, digital humanities. This year marks my twenty-fifth as a full-time professor, and I have seen enough critical schools come and go not to feel skeptical about scholarly rebranding.

My point is not that I am old. Though I am getting older. I have an adult son, I think about retirement, and last week, my lower back wrenched for no apparent reason. But I would ask any young scholar today: Why are you doing this? What’s the relevance? So what? For God’s sakes, I want to tell the occasional grad student who cross my path–focus on what you care about, research what engages you, write how you f*cking want to write.

As From the Fallen Tree (published in 2003) nears its twentieth birthday, thankfully, I remain happy with the book. The prose holds up well and the core issues–the vexed roots of an environmental tradition in the United States–absolutely remain in place. And eighteen years later, I revisit the subject of the Ohio Ordinances in a follow-up, a book that I could not have written as a grad student called A Road Course in Early American Literature.

The Introduction to the Road Course talks about visiting an historian who had published a monograph about the Northwest Territory. My aims for that visit were less than honest. I wanted verification, for sure, but truth be told, I wanted connections that could lead to a grant.

I never did get the grant I wanted. In fact, I would never see the historian again. Instead, I entered a demoralizing job market. Employment looked like a dim possibility. Even Marietta College, a little liberal arts school in Ohio, listed a position … and the school did not give me so much as an interview. Maybe there were other young scholars publishing on the Northwest Ordinance? Who knows??

What I have now is perspective. I am proud of the progress measured by these two books, From the Fallen Tree and the Road Course. The new historicism of the 1990s all too easily served as a clever game, a chance to show off academic moves. I dug the theoretic rigor at the time–I still do enjoy a good scholarly puzzle. With the Road Course, I tried to preserve the same intellectual playfulness. But colonialism remains a serious subject. And the Road Course approaches that high seriousness, I think, with a lot more heart. It should be an obvious point for graduate students, though one we academics often forget. The importance of following your heart.

What I have now is perspective. I am proud of the progress measured by these two books, From the Fallen Tree and the Road Course. The new historicism of the 1990s all too easily served as a clever game, a chance to show off academic moves. I dug the theoretic rigor at the time–I still do enjoy a good scholarly puzzle. With the Road Course, I tried to preserve the same intellectual playfulness. But colonialism remains a serious subject. And the Road Course approaches that high seriousness, I think, with a lot more heart. It should be an obvious point for graduate students, though one we academics often forget. The importance of following your heart.