¿Quien sabe?

St. Pete locals claim a mound called Jungle Prada. A real estate developer and amateur historian Walter Fuller made up this claim, so the city would run a streetcar to property there.

Florida abounds with faux archaeology, a point I make in a recent Orion post. Springs across the state  call themselves the Fountain of Youth, the mythical spring that eluded Ponce de Leon in 1513. Five municipalities around Tampa Bay claim Hernando de Soto, who landed here in 1539. Most of the sites have historical markers. Most of the markers are wrong.

call themselves the Fountain of Youth, the mythical spring that eluded Ponce de Leon in 1513. Five municipalities around Tampa Bay claim Hernando de Soto, who landed here in 1539. Most of the sites have historical markers. Most of the markers are wrong.

Colonial American letters starts from a crisis of claims. When Pánfilo de Nárvaez seizes la Florida on behalf of God and King, the language strains. His chronicler Cabeza de Vaca renders the scene, here in the most recent translation:

The next day the governor raised the standard in Your Majesty’s behalf and took possession of the land in Your royal name and presented his orders and was obeyed as governor just as Your Majesty commanded. I the same manner we presented ours before him, and he obeyed them as required. Then he commanded the rest of the men to disembark and unload the horses that had survived, which were no more than forty-two in number, because the rest of them had perished due to the great storms and long time at sea. And these few that remained were so thin and worn out that for the present we could make little use of them. The next day the Indians from that village came to us. And although they spoke to us, since we did not have an interpreter we did not understand them. But they made many signs and threatening gestures to us and it seemed to us that they were telling us to leave the land, and with this they parted from us without producing any confrontation and went away.

What gave the Spanish authority to claim a new country?

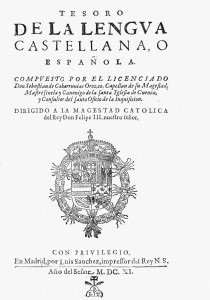

And what of this word, authority? In classes, I emphasize the link between language and empire. Under the entry autor in the first Spanish dictionary, Tesoro de la Lengua  Castellano o Española (1611), the scholar-priest Sebastián de Covarrubias Horozco offers two cognates: autoridad or authority, and the verb autorizar una cosa (to authorize something). An authority carries the weight of Holy Writ. An autoridad, Covarrubias says, provides the basis for “funding a proposition.” Scriveners authorize a document, as on the Pinellas Peninsula in 1528, to ensure its “fidelity.”

Castellano o Española (1611), the scholar-priest Sebastián de Covarrubias Horozco offers two cognates: autoridad or authority, and the verb autorizar una cosa (to authorize something). An authority carries the weight of Holy Writ. An autoridad, Covarrubias says, provides the basis for “funding a proposition.” Scriveners authorize a document, as on the Pinellas Peninsula in 1528, to ensure its “fidelity.”

I slip in a lesson from Covarrubias into my Cabeza de Vaca lecture. I scribble the word on the board, “author.” When an author constructs a past, I remind students, he or she takes ownership of memory. Authors invent; credibility becomes a problem. When we make a payment at the gas station, what does the screen read? The display, we know, says “authorizing.” What does that mean?

Literally, two computers interface to determine the legitimacy of one’s purchasing power. By signing my name, or pecking the date of my wedding anniversary into a keypad, I promise to stand by the withdrawal. The vendor wants to know, is this chump at the pump true to his word?

In Cabeza de Vaca, who speaks for whom? The author stakes his authority in Church and Crown. He dedicates his account to Your “Holy, Imperial, Catholic Majesty.” Arriving in la Florida, the Spaniards take “possession of the country in Your Royal name.” Credentials are shown, titles presented and the ceremony completed, “as was required.”

What of the Indians? First they run away. Then they respond to the gibberish: “And although they spoke to us, since we did not have an interpreter we did not understand them.” For students this line is almost always a laugh, and were it not for genocide, for the tragic run of events that starts with airborne disease and leads to shell mounds used as road fill, the false “authority” would be comic. Cabeza de Vaca describes the flying of colors and statement of purpose, then concedes that verbal cues were unintelligible.

How to bring this point home to students? Have you ever been in the situation, I ask them, when a parent spoke as if you were not present? I describe the holiday letters my mom and dad used to send. I hated those letters. My siblings and I begged our parents to stop. Mom and dad persisted. The Christmas letters stripped us kids of a voice to tell our own story. They lacked fidelity.

The colonizing letters came without “stamp and seal.” For me American literature proceeds from here. From this failure of semantic authority. We spend the next three months, examining how words fracture, bend and fail.

Further Reading? Check out Cabeza de Vaca: Footnote Trail for the scholarship behind this post.