This week marks the four year anniversary of my father’s passing. I will get together with my siblings who live in town. We’ll have breakfast, talk, and continue to unpack.

My father cast a long shadow.

He inhabits quite a bit of the Road Course. He believed with Ralph Waldo Emerson that “to thine own self be true,” or with Thoreau, to “go confidently in the direction of your dreams.” All that Transcendental stuff.

He inhabits quite a bit of the Road Course. He believed with Ralph Waldo Emerson that “to thine own self be true,” or with Thoreau, to “go confidently in the direction of your dreams.” All that Transcendental stuff.

My parents flipped the bill for four years at Dickinson College–running up a debt, never once telling me what to study or asking what I would do with the degree. My dad wanted only for his children to “go confidently in the direction of their dreams.” He believed strongly in personal freedom. But that same sense of freedom came with a catch. My dad was convinced that he could decide which rules applied to him.

Much of my Road Course follows an ethos of the open road.

In the Preface, my family and I stop at a gated community on St. Simons Island, Georgia. To open the gate, I called a realtor on the phone box. Using “my father’s voice,” an accent of white privilege, I explain in the preface, I obtained the secure combination. The gate slid open.

More than most white people care to admit, a suburban syntax opens doors that otherwise remain closed. That point is documented, even taught in school, for those who care to listen. But what does one lose with a cavalier dismissal of rules?

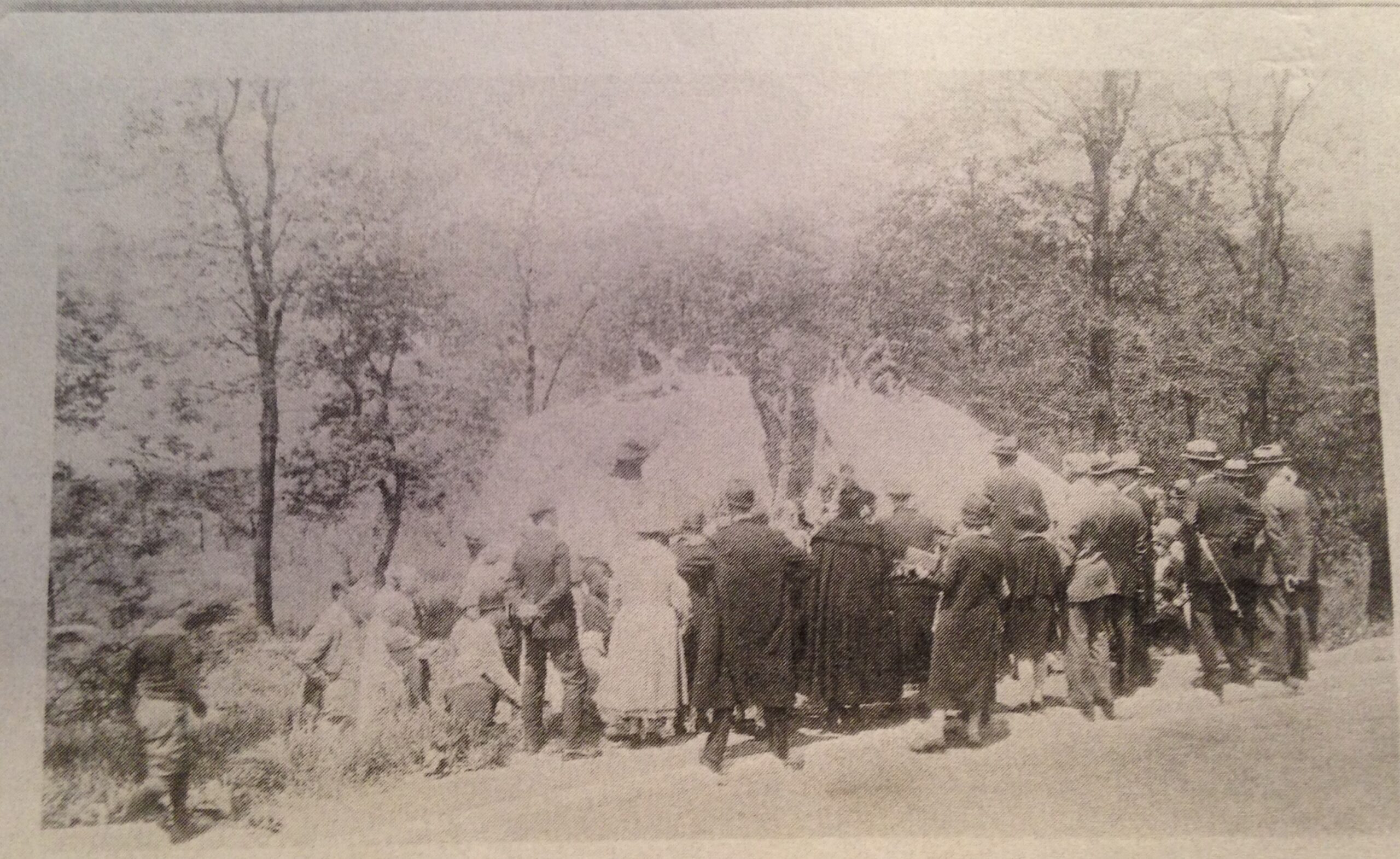

Early twentieth century visitors to Split Rock, on the Bronx-Westchester line, where Anne Hutchinson was then thought to have been killed. (Courtesy, New-York Historical Society)

I explore how freedom isolates in Chapter 10 of the book, “Emerson on the Hutch.” This essay looks at Ralph Waldo Emerson and Puritan martyr Anne Hutchinson through the New York suburb where I grew up. I also reflect upon about my father’s womanizing; by far, this chapter was the most emotionally difficult for me to write in the entire book.

Like almost every man I have ever met, my dad thought with his dick. Most guys learn to check their excesses at some point, which allows them to participate more fully in polite society. Into his seventies, however, my father was still chasing women–secretaries, old flames, strangers on the train. My dad thought with his dick, popped Viagra, and thought he was a genius.

Caveat. The purpose of “Emerson on the Hutch” was never to air dirty laundry. The essay sets a story against Emerson, Puritan theology (particularly a Covenant of Grace versus Covenant of Works), and a post-Victorian landscape of bougie entitlement.

The chapter works. The hybrid personal-scholarly approach, with some pretty solid literary sleuthing (recovering how Emerson was read in 1950s college classrooms) sheds insight into how literature shapes our understanding of place, and how place informs the way we read.

But as I finished up the book, early critics pointed out an uncomfortable truth–that I carry around the same privilege.

A child never separates from the parent. That’s what makes mourning difficult; as we peal back the feelings, positive and negative, we find flecks of our own being.

With the Road Course, I struggle constantly between revelation and what needed to be said. I remain grateful to my parents, who left it to to their children to seek out their own truths. What did I give in return?

I will always be my father’s son.