When the planes hit the towers, I thought, I was prepping a class. In my head we were reading Mary Rowlandson’s Sovereignty and Goodness of God, a 1682 account of a minister’s wife held captive during King Philip’s (or Metacom’s) War. But trauma has a way of sharpening memory and sending it down the wrong path.

When the planes hit the towers, I thought, I was prepping a class. In my head we were reading Mary Rowlandson’s Sovereignty and Goodness of God, a 1682 account of a minister’s wife held captive during King Philip’s (or Metacom’s) War. But trauma has a way of sharpening memory and sending it down the wrong path.

I remember this much. The USF campus, where I was adjuncting at the time, declared a state of emergency. I gathered up my books and walked down the main stairwell. At the lobby landing were big televisions, strapped onto carts, where I first saw the footage of the collapsing Twin Towers.

I also remember how the same footage cycled on an endless loop over the next few weeks, and how the grief quickly gave way to patriotic cant, exploited by the president for American oil.

I responded to the verbal fallout as an English teacher should, I thought, relating current events back to class. My students, now with some grounding in colonial letters, compared the earlier centuries with our own. They had read Puritan narratives of the chosen race, seen how Boston’s “City on a Hill” led to Indian wars, and were poised to recognize the rhetorical slippage from politicians today.

I gave my class a transcript of George W. Bush’s address to the nation on September 12th, a moving and well-crafted speech that pit the attacks on the Twin Towers and the Pentagon as Good versus Evil. “Terrorists can shake the foundations of our biggest buildings,” Bush declared, “but they cannot touch the foundations of America.” With skillful use of the passive voice, he glossed motives: “America was targeted for attack because we’re the brightest beacon for freedom and opportunity in the world.” In place of explanation, Bush recycled language right out of the Crusades, or Puritan pronouncements of the chosen people. He closed with a snippet from Psalms, consoling a shaken nation:

Tonight I ask you for your prayers for all those who grieve, for the children whose worlds have been shattered, for all those whose sense of safety and security has been threatened. And I pray they will be comforted by a power greater than any of us, spoken through the ages in Psalm 23: ‘Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I fear no evil for you are with me.’ [….]

None of us will ever forget this day, yet we go forward to defend freedom and all that is good and just in our world.

Thank you. Goodnight and God bless America.

Bad things happen when a nation presumes God to be on its side.

Rowlandson’s Sovereignty and Goodness of God (which, in fact, I was not teaching that fateful week) cautions us about lining ourselves up with The Big Guy Upstairs. Metacom’s War was caused by decades of English colonization, land grabbing and environmental change; the Indians did not hate the white man, I tell students, so much as the white man’s cow. Mary, wife of minister Joseph Rowlandson, penned an account of her three-month captivity at some point after her “redemption.” The minister and colonial lobbyist Increase Mather then tacked on a Preface, spinning her story of individual trauma into the exemplum of corporate mission, where God favors His chosen through Trial.

No manuscript survives, so we are left to guess where Rowlandson’s words stop and where Mather begins. Twenty short, Bible-brined “Removes” (or chapters) in The Sovereignty and Goodness of God cast doleful challenges as evidence of Grace.

Brute hardship grounds the tale. On this page, torn down the right corner, Rowlandson describes leaving her dead baby in the woods:

About two houres in the night, my sweet Babe like a Lamb, departed this life, on Feb. 18, 1676, It being about about six years and five months old. It was nine dayes from the first wounding, in [a] miserable condition, without any refreshing of one nature or other, except a little cold water. I cannot but take notice, how at another time I could not bear to be in the room where any dead person was, but now the case is changed; I must and could ly down by my dead Babe, side by side all the night after. I have thought since of the wonderfull goodness of God to me, in preserving me in the use of my reason and senses, in that distressed time, that I did not use wicked and violent means to end my own life: In the morning, when they understood that my child was dead, they sent for me home to my Masters Wigwam: [by my Master in this writing, must be understood Quanopin, who was a Saggamore, and married King Philips wives Sister; not that he first took me, but I was sold to him by another Narraganset Indian, who took me first [illegible] of the Garrison] I went to take [illegible,] child in my arms to carry it with me ….

About two houres in the night, my sweet Babe like a Lamb, departed this life, on Feb. 18, 1676, It being about about six years and five months old. It was nine dayes from the first wounding, in [a] miserable condition, without any refreshing of one nature or other, except a little cold water. I cannot but take notice, how at another time I could not bear to be in the room where any dead person was, but now the case is changed; I must and could ly down by my dead Babe, side by side all the night after. I have thought since of the wonderfull goodness of God to me, in preserving me in the use of my reason and senses, in that distressed time, that I did not use wicked and violent means to end my own life: In the morning, when they understood that my child was dead, they sent for me home to my Masters Wigwam: [by my Master in this writing, must be understood Quanopin, who was a Saggamore, and married King Philips wives Sister; not that he first took me, but I was sold to him by another Narraganset Indian, who took me first [illegible] of the Garrison] I went to take [illegible,] child in my arms to carry it with me ….

A teacher’s job is to peal back the layers of a complicated text. Start with the hurt. Mary (for some reason students use first names with female authors) buries her baby in a wilderness and contemplates suicide. Later scenes evoke more contradictory or dissonant reactions (the half-starved Rowlandson steals food from an Indian child). Elsewhere the “savages” are not all that “savage.” They feed Rowlandson, they give her a Bible, and the captive trades meat and “ground nuts” for seamstress work. I remind students that a Nipmuc named James Printer actually set the type to this book. How must James have felt, I ask hypothetically, setting pages that aligned one’s own race with the Devil? For Rowlandson, the natives are tools in the test of faith: “I have often thought since of the wonderful goodness of God to me ….”

War needs an enemy. Wartime leaders need stories to invent motivations. As we create a plot, we also simplify the enemy’s rationale. War is also serious business (I say this will full respect to American veterans, many of whom go on to take courses in early American literature with windbags like me). If we are to expend our national and human treasury, we should know who we are attacking — and why.

To even consider al Qaeda‘s perspective after September 11th smacked of heresy. But on October 7, 2001, Osama bin Laden explained himself to the world. Spurred by the first U.S. strikes against Afghanistan, the al Qaeda operative described September 11th as retaliation — as a reaction to persecution in Palestine, the 1996 invasion of Iraq and decades of meddling in the Middle East. “And what America is facing today,” he claimed, “is something very little of what we have tasted for decades.” The United States has “supported the murder against the victim,” bin Laden claimed, “so God has given them back what they deserve.”

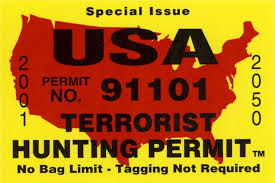

What do I say to this? As one who has lived in both New York and the Deep South, I was always wary of the nation-wide sympathy — the “Terrorist Hunting Permits” on pickup trucks. Since when did all those Good Old Boys from Georgia to Texas care about Yankees anyway?

What do I say to this? As one who has lived in both New York and the Deep South, I was always wary of the nation-wide sympathy — the “Terrorist Hunting Permits” on pickup trucks. Since when did all those Good Old Boys from Georgia to Texas care about Yankees anyway?

Let’s set aside the ridiculous assertion (extremist under any religious stripe) that God sanctions murder as just desert. The Sovereignty and Goodness of God presents us with a more difficult question: where we locate our sympathies? If we grieve for devastated families in metro New York, do we extend the same for the children of Baghdad? And what about Puritan New England? The Indians who burned down Mary Rowlandson’s home and held her hostage resented the loss of their land. If we take bin Laden at his word, we can glimpse the sources of his anger — smoldering resentment over Israel, the military bases in holy Saudi Arabia and the 1996 invasion of Iraq. The cant of “our freedoms” sounds shrill by comparison. September 11th was a counterattack.