We were two eggheads in love, young and partially employed. I had just finished my dissertation about nature and frontier writing in the early United States. An undistinguished career awaited. No fellowships. No job. Julie needed a year to on finish her own thesis, and she was paying ridiculous rent in Manhattan. We were stuck on the adjunct track, soon to join New York City’s vast intellectual underclass — the great ranks of half-washed scholars who lurk outside the steps of the Public Library on frosty February mornings, waiting for the reading room to open; who piece together part-time gigs at the most distant of outerborough campuses; who hide pricey university press titles in the Strand Bookstore basement, until their next paycheck comes. We needed a change of place.

So we moved to Philadelphia. Rents were cheaper. We found an apartment with a patio and fireplace, within walking distance of Independence Hall. I worked as a file clerk for a medical lab in Valley Forge, battling rush-hour traffic on the Schuylkill Expressway and squeezing in part-time hours as a writing tutor. Julie chipped away at her dissertation while temping at the University of Pennsylvania Hospital — answering phones for a real doctor.

We saved up money for conferences, ignoring a ballooning credit card debt. Early one Spring, we traveled to Virginia. Julie had a paper to give in Richmond. We would be in the area, so I scheduled an appointment with an historian at UVa. The historian and I had corresponded occasionally. I wrote him about early territorial government in the United States; he gave me a long critique (single spaced, ten point pica font) of my dissertation proposal, demolishing my argument. I wanted to thank the historian. Maybe angle for a grant.

We pulled into Charlottesville. It was a lesson in the scholarly have-and-have-nots. Julie found a spot to read in the heart of Thomas Jefferson’s leafy “academic village.” I met the historian in his office just off the lawn. He gave me coffee and some reading tips; no promises for a grant, but encouragement. “What will you do to make this a brilliant book,” he asked, not a trace of irony in his voice. I fumbled. Our thirty minutes passed quickly. The historian’s next appointment materialized from the shrubbery outside the office. He threw open a massive casement window, shouted “hello” into the garden. “These are nice,” he said, tapping his knuckles against the casement’s white satin trim.

We pulled into Charlottesville. It was a lesson in the scholarly have-and-have-nots. Julie found a spot to read in the heart of Thomas Jefferson’s leafy “academic village.” I met the historian in his office just off the lawn. He gave me coffee and some reading tips; no promises for a grant, but encouragement. “What will you do to make this a brilliant book,” he asked, not a trace of irony in his voice. I fumbled. Our thirty minutes passed quickly. The historian’s next appointment materialized from the shrubbery outside the office. He threw open a massive casement window, shouted “hello” into the garden. “These are nice,” he said, tapping his knuckles against the casement’s white satin trim.

Nothing else came of the meeting. Julie’s paper was fine. (She found her own niche in time, as a Civil Rights scholar.) Before heading home, we made one more stop.

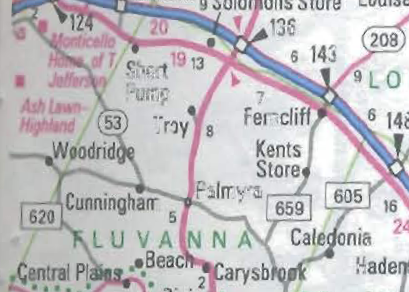

I noticed a dot just outside Charlottesville in our Rand McNally, a town called Solomons Store. (Cut off, up top.) The name brought to mind Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon. In this novel the main character Milkman Dead journeys South, searching for his roots. His car dies in the Virginia Piedmont, outside a store owned by Mr. Solomon, a “light-skinned Negro with red hair turning white.”

I noticed a dot just outside Charlottesville in our Rand McNally, a town called Solomons Store. (Cut off, up top.) The name brought to mind Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon. In this novel the main character Milkman Dead journeys South, searching for his roots. His car dies in the Virginia Piedmont, outside a store owned by Mr. Solomon, a “light-skinned Negro with red hair turning white.”

The Jefferson allusion hit us hard. We convinced ourselves that Morrison was referencing another lawgiving Virginian — our nation’s Solomon, father of red-headed, light-skinned children. We had to stop.

Julie drove. I navigated, the Rand McNally spread open on my lap. We exited at Solomons Store but found no town. We pulled into a gas station for directions. (These were the days before one paid at the pump.) I stood in line and asked the clerk. He had no clue. A local looked over our atlas. No one recognized Solomons Store. We had a cartographic mystery on our hands.

Back in Philadelphia, Julie wrote Rand McNally, in Skokie, Illinois. “On a recent trip to the area,” she asked, “I looked for Solomons Store and did not find it.” She closed playfully: “Thank you for your great maps …. I’m a car dog and use them all the time.” (Henceforth the name, Car Dog.)

Back in Philadelphia, Julie wrote Rand McNally, in Skokie, Illinois. “On a recent trip to the area,” she asked, “I looked for Solomons Store and did not find it.” She closed playfully: “Thank you for your great maps …. I’m a car dog and use them all the time.” (Henceforth the name, Car Dog.)

A public relations person responded: “Solomons is a town of 150 people … located north of Richmond, Virginia in Henrico County on US 1 south of I-295. The error that you found in the 1995 edition of the atlas has been corrected with the publication of the 1996 edition.”

A year passed. Rand McNally published a new atlas. I logged a couple thousand miles with Julie (now Car Dog), tearing the cover of our atlas from its pages. We bought the 1996 edition. Sure enough, the company had moved Solomons Store to Richmond.

A year passed. Rand McNally published a new atlas. I logged a couple thousand miles with Julie (now Car Dog), tearing the cover of our atlas from its pages. We bought the 1996 edition. Sure enough, the company had moved Solomons Store to Richmond.

Then a miracle. We landed full-time teaching jobs. Car Dog and I married. With family and friends still up North, we drove through Richmond regularly. Solomons Store never left our thoughts. On one trip north, we skipped the bypass and took the beltway. Following the directions from Rand McNally, “Henrico County on US 1 south of I-295,” we found nothing. We saw a gas station and an Arby’s, but no town to speak of.

Undeterred, Car Dog contacted Henrico County. The county historian responded. “Solomon’s Store is an actual location,” he wrote, “although no structures survive today.” The town “does appear on a 1905 property map,” he gamely advised, and a “study of the deeds, census and tax records might provide more information about the family and their store.”

Car Dog saved the letters and put them in a red folder. She filed the folder. She and I played career hopscotch for ten peripatetic yeas — job for me and trailing spouse for her, then a job for her, and vice versa. Work took us from south Georgia to Florida to Mississippi then back to Florida. Car Dog cultivated other projects and gave me the red folder. My dissertation became a book (maybe not brilliant but published), prompting a colleague at the University of Richmond to invite me for a campus talk. I used a free morning to check out the Virginia Historical Society and solve the mystery of Solomons Store. Three hours in the archives uncovered nothing of note. It was time to call this case closed.

Sort of. As anyone who knows Toni Morrison can tell you, Song of Solomon takes lost place as one of its central themes. The novel opens memorably outside Mercy Hospital, or “No Mercy Hospital,” on “Not Doctor Street.” Morrison gives the backstory to “Not Doctor Street” in a mocking aside. City maps officially list the thoroughfare as “Mains Avenue,” but the black community called it “Doctor Street” because the town’s only black doctor lived there. Any confusion was ignored, at least until the draft board got involved, leading officials to issue this “genuinely clarifying” notice: “that the avenue running northerly and southerly from Shore Road fronting the lake to the junction of routes 6 and 2 leading to Pennsylvania, and also running parallel to and between Rutherford Avenue and Broadway, had always been and always will be known as Mains Avenue and not Doctor Street.”

The official pronouncement, Morrison wryly concludes, “gave Southside residents a way to keep their memories alive and please city legislators as well.” Small matter of capitalization aside, the two parties could agree on one name. “Not Doctor Street.”

The rest of the novel riffs off this opening scene. From Milkman’s birth at No Mercy Hospital until the end, where he either jumps to his death or flies back to Africa, the story unfolds around details of lost geography and place. Like Thomas Jefferson two hundred years earlier, Morrison explores identity through space.

Milkman’s quest starts from a mysterious source: the lyrics Sugarman done fly away, sung by his Aunt Pilate on the day he was born, outside the hospital. The misremembered song leads Milkman to the Virginia Blue Ridge, where his car breaks down in front of Solomon’s store. This town was not on his Texaco road map, Morrison explains: and the AAA office couldn’t give a nonmember a charted course — just the map and some general information. Even at that, watching as carefully as he could, he wouldn’t have known he had arrived if the fan belt hadn’t broken right in front of Solomon’s General Store, which turned out to be the heart and soul of Shalimar, Virginia.

A semi-conscious landscape of myth trumps the Texaco road map. Literary and literal geographies part ways in the search for more redemptive terrain. Milkman does not know where he is himself until a fan belt snaps; he fails to realize he is even there, in Shalimar, until he wanders the woods during an archetypal hunt, learning the language of trees, reading words physically, “through his fingers,” in black transcendence, “like the blind man who caresses a page of braille.”

Language becomes tactile. Words grow bark. The fragments of a lost topography cohere once Milkman Dead learns to link letters and things. The epiphany follows a pilgrimage across space, real and imagined, into the deeper latitudes of myth. “How many dead lives and fading memories were buried in and beneath the names of the places in this country,” Milkman wonders, “the real names of people, places, and things.” Hidden from view, these names “had meaning.”

Cue up A Road Course in American Literature. Places do not yield their stories in an orderly manner. A fan belt snaps; we need disciplined luck. Car Dog and I passed the phantom town of Solomons Store just as Toni Morrison’s reputation was peaking, when academics were formulating their own ideas about erasure, memory, and space. My reading of Jefferson through Morrison was not such a stretch after all. Books lead us into the hidden corners of a landscape’s memory.

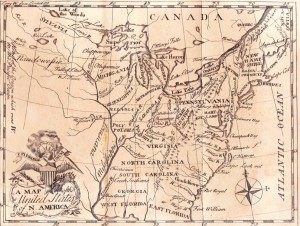

Johann David Schopf, after Henry Pursell, A MAP of the United States of N. AMERICA (1788).

In the 1780s Jefferson chaired a congressional committee that authored the first “blueprint” for territorial government in the Middle West. (I discussed territorial government with the historian in Charlottesville.) Long story short, Jefferson’s committee issued the first in a series of documents that effectively colonized a continent — the Congressional “Report” of 1784, the Land Ordinance of 1785 and the Northwest Ordinance of 1787. These acts divvied up the land, made it fungible, and outlined provisional governments that brought fractious border regions within the fold of an expanding republic. From this same Euclidian order we get the squared state boundaries, laid roughshod over the terrain, that came to define the American West. Jefferson contributed the names — Sylvania, Metropotamia, Cherronesus.

In the same decade he sat on the Ohio ordinance committee, Jefferson also wrote a book, Notes on the State of Virginia. This literary exercise defines the state geographically. Notes on Virginia opens with a map, co-authored by his father, Peter Jefferson. The book has twenty-three chapters, or “Queries.” The first is “Boundaries”; the rest fill those boundaries in. Here is the book’s opening sentence: Virginia is bounded on the East by the Atlantic: on the North by a line of latitude, crossing the Eastern Shore through Watkin’s Point, being about 37o. 57′ North Latitude; from thence by a streight line to Cinquac near the mouth of the Patowmac, which is common to Virginia and Maryland, to the first fountain of its northern branch; thence by a meridian line.” And so on.

Lines, latitudes and meridians kick things off. In the chapters that follow, Jefferson then tears through the shelves of his celebrated library, offering a small scale model of “civilized” Virginia. Drawing from geology, zoology, archaeology, ethics and law, even literary criticism, Jefferson sets his thematic compass around two basic questions: What society suits the physical landscape, and who deserves a place there?

Native Americans fare well in this exercise. Blacks, not so much. As evidence of indigenous potential to join whites as future partners in the republic, he cites a well-traveled speech by an Ohio Indian named “Tahgajute,” or Logan, who challenges the whole “orations of Demosthenes and Cicero.” Equivalent efforts by African Americans receive a flat dismissal. Among slaves “is misery enough,” Jefferson pronounces, “but no poetry.”

Two decades later, I am still on the road — following Milkman Dead and the misguided, red-headed lawgiver. Our “more perfect union” starts with a poetics of space.