How do you publish a book with an academic press? The question starts with one of the true mysteries of scholarly life: peer review. The already exhausted author, having toiling for years on an obscure topic that interests only distant peers and the closest of friends, queries an editor. If the editor thinks the project has potential, then she (I have always worked with female editors), sends the manuscript out for review. These reviewers typically come from different backgrounds, academically and personally, and rarely does the double-blind process yield even results. Along with helpful critiques, the expectant author receives a “publish,” “reject,” or “revise and resubmit.”

How do you publish a book with an academic press? The question starts with one of the true mysteries of scholarly life: peer review. The already exhausted author, having toiling for years on an obscure topic that interests only distant peers and the closest of friends, queries an editor. If the editor thinks the project has potential, then she (I have always worked with female editors), sends the manuscript out for review. These reviewers typically come from different backgrounds, academically and personally, and rarely does the double-blind process yield even results. Along with helpful critiques, the expectant author receives a “publish,” “reject,” or “revise and resubmit.”

The process is always fraught, and for the Road Course, even painful. A double-blind review presumes objectivity, that two individuals can (apart from individual bias or opinion) reach an objective conclusion about the knowledge being presented. While the Road Course incorporates quite a bit of literary scholarship, an entire career of reading honestly, my approach is anything but objective. The use of story-telling and personal narrative instead took me down a decidedly subjective path–which, fair enough, clashed with the principles of peer review. Where a manuscript would typically be judged on its evidence or strength of analysis, my incorporation of the personal voice meant that some judgement would be made to me as … well … a person. I was fine with that. Long ago, I subscribed to the notion that teaching in the “contact zone” (to borrow Mary Louise Pratt’s term) means we all put ourselves at risk. We expose our vulnerabilities. In my own case, being a white male, meant coming to grips with my own whiteness and deep-seated sexism. Peer review meant rooting out these internal biases. And I would be lying if I said this almost dental rooting did not hurt.

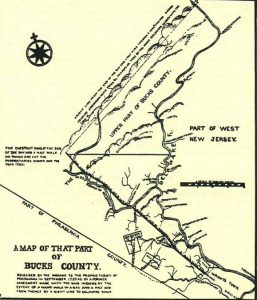

Which leads me to the Walking Purchase. The “hurry walk” of 1737, a deal between the colony of Pennsylvania and the Lenni-Lenape (or Delaware) Indians, represents a nadir in a long and ignoble history of American land swindles. Based on the spurious record of an agreement by William Penn, Pennsylvania claimed a tract of land in southeastern Pennsylvania that would be meted out by a day-and-a-half long walk. The colonists not only changed the direction of this walk, to appropriate more terrain, but broke the spirit of the supposed agreement by clearing a path and appointing three of its fastest “walkers” to measure out the claim. On September 19, 1737, three walkers set out from the Wrightstown Meeting House (across the Delaware River from Trenton), moving at a clip that drew immediate protests from the Lenni-Lenape. The runner with the greatest endurance, Edward Marshall, reached the present-day village of Jim Thorpe, sixty miles away. The surveyors drew up their plats, the Delawares rightly cried foul, and native-white relations on the Pennsylvania suffered for decades.

Which leads me to the Walking Purchase. The “hurry walk” of 1737, a deal between the colony of Pennsylvania and the Lenni-Lenape (or Delaware) Indians, represents a nadir in a long and ignoble history of American land swindles. Based on the spurious record of an agreement by William Penn, Pennsylvania claimed a tract of land in southeastern Pennsylvania that would be meted out by a day-and-a-half long walk. The colonists not only changed the direction of this walk, to appropriate more terrain, but broke the spirit of the supposed agreement by clearing a path and appointing three of its fastest “walkers” to measure out the claim. On September 19, 1737, three walkers set out from the Wrightstown Meeting House (across the Delaware River from Trenton), moving at a clip that drew immediate protests from the Lenni-Lenape. The runner with the greatest endurance, Edward Marshall, reached the present-day village of Jim Thorpe, sixty miles away. The surveyors drew up their plats, the Delawares rightly cried foul, and native-white relations on the Pennsylvania suffered for decades.

Chapter Five of the Road Course retraces the Walking Purchase, which brings me back to the subject of peer review. Ignoring the advice of more informed hiking groups, I wanted to see if I could retrace the 1737 route. Our kid was at camp in the Delaware Water Gap, and my wife Julie had grading to finish for a summer course, so I started the “hurry walk” at my own pace (taking three days, twice the time of the earlier walkers’ frenetic clip). Julie agreed to shuttle me through stretches of the highway where I could become road kill. On the third day, she settled into a little B&B in Jim Thorpe, where we booked a romantic suite with Jacuzzi tub–and which I reached, drenched and exhausted.

The owner of the B&B, a history buff, gave us a bottle of white wine to conclude the trip. After 60 miles I could not reach my feet. Julie helped me peal off soaked socks, poured two glasses of wine, stripped, and joined me in the Jacuzzi. And here my peer reviewer lost it. My wife is an accomplished scholar of Civil Rights literature, a full professor and fantastic teacher, far more valued at our university than I am. So why should I describe her in the bathtub?

The reviewer pointed out nettlesome examples of my blind sexism–habits in my personal life that had bled into my literary analysis. Earlier versions of the manuscripts did not use Julie’s name, she was “Car Dog,” and while Julie happened to like that name (the book’s Introduction explained the inside joke), the external reader found the nickname demeaning. Likewise, my enraged reviewer wanted to know, why did I not situate Julie’s stellar scholarly more deeply within my own study? As I reworked the Road Course, both changes were easy to make. The name required a simple “search and replace,” and having read almost every page that Julie has ever published, I could easily hang flesh and bones on her scholarship.

Chapter Five of the Road Course was area where I could make the change, bringing to bear the critiques from my external reviewer. Here was the chapter ended in the first draft: I collapsed in the bathroom. Car Dog ran hot water in the tub. She poured two glasses of wine, unlaced my filthy shoes, pealed off my mud-caked socks, and helped manage the soaked pants past my ankles. I could not summon another step. I had never felt so relieved to find myself out of the woods, in the safe comfort of a woman’s space. I was too tired for anything. My story was over. Car Dog stripped, toasted my endurance, and with nothing left to say, she joined me in the hot Jacuzzi tub.

The revised version puts clothes back on my wife and recognizes how, even after my walk, I still owed her a romantic dinner in Jim Thorpe: I ran hot water for the tub and unlaced my boots. I could no longer reach past my knees. Julie helped me peel off the mud-caked pants and thick, wet socks. We soaked in the Jacuzzi, long enough us polish off the wine, then dressed in our nice clothes. I hobbled back down the carpeted steps, clinging to the banister, worn to the nub by an academic exercise. I could no longer walk but I was in no position to renege on our date. I would make good on my promise for a romantic dinner. Exhausted, I summoned those few last steps.

Honestly, I do not recall who actually ran the bath. But other changes reflect, I hope, a shift in emphasis. In the revised version “Car Dog” is now Julie; we still soak in the tub, but the action focuses on getting dressed; and where the first ending says I could not muster another step, in truth, I hobbled down the steps to make good on Julie’s promised dinner date.

This revised ending marks just one point where I tried to confront my own unwoke sexism. The changes followed double-blind review, and while I am certain that my reviewer still holds reservations about the Road Course, the process certainly saved me from far greater criticism in publication. In my attempt to weave together personal narrative and cultural-literary analysis, moreover, I left myself vulnerable. Double-blind review is designed to clear out errors in thought and analysis of the evidence. But what happens when I present as evidence scenes from my own life? What errs, in this case, was not my interpretation of a given literary text but actually my own marriage.

I’m good with that critique. The Road Course uses the personal to address two shortcomings in current literary scholarship. The first, of course, is the myth that scholarship should be strictly analytic, as if fiction or poetry or drama were best understood through the lens of the social sciences. Nothing could be more absurd, of course, and as humanities funding now dies on the vine, I suggest a scholarly return to narrative–to stories. The second involves political posturing. Fairly or not, English professors have been accused of self-righteous posturing. Critics less charitably call out the political correctness, and while I have no problem with the aspirational nature of criticism, the goal of reading has always been to draw out the best that has been thought and said, professional criticism smacks of insincerity. Academics talk at professional gatherings as if their own intellectual-moral transformation occurred sui generis, as if they emerged from the womb having already read bell hooks and Michel Foucault. Meanwhile the sharks circle, when a well-known scholar makes a predictable gaffe.

Far better as a white male scholar, then, to acknowledge my own privileges of race and gender and class. Why not speak to my blind sides? But if this Road Course has done its office, met its goal, then it acknowledges my own need for growth. I teach the American survey under the naive assumption that we can make the United States a more perfect union. That path to improvement starts with me.