Curiosity: Thomas Jefferson through Toni Morrison (Lesson 2)

Toward the end of Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon, the main character Milkman Dead experiences an epiphany. Once a lost traveler, he considers the meaning behind the names of places where he has lived. “He read the road signs with interest now, wondering what lay beneath the names. The Algonquins had named the territory he lived in Great Water, michi gami. How many dead lives and fading memories were buried in and beneath the names of the places in this country. Under the recorded names were other names …. recorded for all time in some dusty file, hid from view the real names of people, places, and things.” These names,” Milkman realizes, “had meaning.”

Toward the end of Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon, the main character Milkman Dead experiences an epiphany. Once a lost traveler, he considers the meaning behind the names of places where he has lived. “He read the road signs with interest now, wondering what lay beneath the names. The Algonquins had named the territory he lived in Great Water, michi gami. How many dead lives and fading memories were buried in and beneath the names of the places in this country. Under the recorded names were other names …. recorded for all time in some dusty file, hid from view the real names of people, places, and things.” These names,” Milkman realizes, “had meaning.”

When we think of “civic values,” the term “curiosity” may not leap to mind. But the topic was huge during the Revolutionary era. How can we decide what is best for our society if we do not learn the details about where we live? How can people govern if we are not curious about the world?

In Thomas Jefferson’s rightly maligned though foundational book, Notes on the State of Virginia, he tries to understand the state from a series of different scholarly perspectives. He entertains the academic disciplines of law, natural history (or science), geography, ethics, archaeology, even literary criticism to ask what sort of state should Virginia become? The results are uneven, his attempt to rationalize slavery particularly troubling, though the search itself can be instructive.

Jefferson’s Notes came during a moment of settler-colonization of North America, as the United States developed a mechanism for claiming and controlling Toni Morrison’s native Midwest. Jefferson sat on a congressional committee that drafted one of the Northwest Ordinances, Jefferson’s own contribution being a series of ridiculous names — Sylvania, Metropotamia, Cheronesus. Thankfully these names disappeared into the “dusty file” that Morrison describes. But it’s worth asking: what histories lie behind a toponym, or place name? How has the place where you lived been divvied up? Exploited? Understood? What are the different academic tools that can help you better understand a place? What insight do they yield — and how do the different intellectual tools fall short? When do you drop one tool and turn to another? Can you adopt Jefferson’s intellectual method without repeating the imperative of colonization?

Jefferson’s Notes came during a moment of settler-colonization of North America, as the United States developed a mechanism for claiming and controlling Toni Morrison’s native Midwest. Jefferson sat on a congressional committee that drafted one of the Northwest Ordinances, Jefferson’s own contribution being a series of ridiculous names — Sylvania, Metropotamia, Cheronesus. Thankfully these names disappeared into the “dusty file” that Morrison describes. But it’s worth asking: what histories lie behind a toponym, or place name? How has the place where you lived been divvied up? Exploited? Understood? What are the different academic tools that can help you better understand a place? What insight do they yield — and how do the different intellectual tools fall short? When do you drop one tool and turn to another? Can you adopt Jefferson’s intellectual method without repeating the imperative of colonization?

Lesson: Track down the history to the name where you live. Does the name honor a particular person, feature, history or place? Once you know the story, how comfortable do you feel with that story? Who in the past has inhabited where you live? When were boundaries created and how do they divide today? How can you stake a claim to place that holds more meaning? Make the case for a new name.

Freedom: from African American Spirituals (Lesson 1)

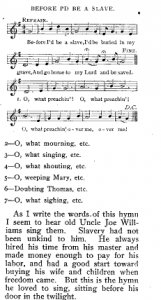

In 1899 the New England Magazine published a transcription with music of the great African American spiritual, “Oh Freedom.” The author cites a man named Joe Williams, who had purchased freedom for himself and his family, and who loved to sing this song “before his door in the twilight.”

In 1899 the New England Magazine published a transcription with music of the great African American spiritual, “Oh Freedom.” The author cites a man named Joe Williams, who had purchased freedom for himself and his family, and who loved to sing this song “before his door in the twilight.”

According to many accounts, enslaved Igbos sang “Oh Freedom” when they jumped ship off St. Simons Island in 1804. The song was adopted by civil rights workers during the 1960s. This hymn has taken many turns, shifting with the long struggle of African American justice–from the early days of slavery, through classic discussions like W.E.B. DuBois’ “Of the Sorrow Songs,” to our nation’s recent (and ongoing) struggle for voting rights.

Lesson: Review the first “lyra Africana,” Slave Songs of the United States, published in 1867. Find songs you may know in this volume, and look for other musical expressions of freedom. How does the song remain the same? When, why, and where do versions differ? What does it mean, in the words of literary critic William Andrews, to tell a free story? Sing as a class those freedom songs you find most inspiring.

Lesson: Review the first “lyra Africana,” Slave Songs of the United States, published in 1867. Find songs you may know in this volume, and look for other musical expressions of freedom. How does the song remain the same? When, why, and where do versions differ? What does it mean, in the words of literary critic William Andrews, to tell a free story? Sing as a class those freedom songs you find most inspiring.

Note: Lessons on this page take their cue from Florida Senate Bill 146, “Civic Education,” calling for nonpartisan curriculum in civic literacy. The following 12 Lessons draw from foundational texts in early America, providing working teachers with material and prompts for meaningful classroom discussion.