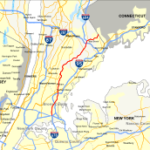

In setting Ralph Waldo Emerson on the Hutchinson River Parkway, this chapter takes on two of the more exhausted topics of American history and culture. With both, the intrepid scholar could read for months and barely scratch the surface. To make matters still worse, the topic of suburban sprawl claims its own space on library shelves. For context on Pelham and Westchester County, I rely on Kenneth Jackson’s Bancroft-winning Crabgrass Frontier: Suburbanization of America (1985); on Pelham’s golf courses and accoutrements, see Lockwood Barr’s breezy though factually reliable A brief, but most complete & true Account of the Settlement of the Ancient Town of Pelham, Westchester County, State of New York (1946). On Westchester County and the parkway system, I draw from the searchable New York Times database; internal literature, such as the Report of the Westchester County Park Commission for the Acquisition of Parks, Parkways or Roadways (1923); and from Robert Bolton, The History of the Several Towns, Manors and Patents of the County of Westchester …. (1881). Reginald Pelham Bolton speculates on the location of Hutchinson’s home in the Bronx in “The Home of Mistress Ann[e] Hutchinson at Pelham, 1642-43” (1922), though he backs away from his earlier speculation in his book, A Woman Misunderstood (1931). Blake A. Bell carries on the long antiquarian tradition with his “Historic Pelham” blog.

In setting Ralph Waldo Emerson on the Hutchinson River Parkway, this chapter takes on two of the more exhausted topics of American history and culture. With both, the intrepid scholar could read for months and barely scratch the surface. To make matters still worse, the topic of suburban sprawl claims its own space on library shelves. For context on Pelham and Westchester County, I rely on Kenneth Jackson’s Bancroft-winning Crabgrass Frontier: Suburbanization of America (1985); on Pelham’s golf courses and accoutrements, see Lockwood Barr’s breezy though factually reliable A brief, but most complete & true Account of the Settlement of the Ancient Town of Pelham, Westchester County, State of New York (1946). On Westchester County and the parkway system, I draw from the searchable New York Times database; internal literature, such as the Report of the Westchester County Park Commission for the Acquisition of Parks, Parkways or Roadways (1923); and from Robert Bolton, The History of the Several Towns, Manors and Patents of the County of Westchester …. (1881). Reginald Pelham Bolton speculates on the location of Hutchinson’s home in the Bronx in “The Home of Mistress Ann[e] Hutchinson at Pelham, 1642-43” (1922), though he backs away from his earlier speculation in his book, A Woman Misunderstood (1931). Blake A. Bell carries on the long antiquarian tradition with his “Historic Pelham” blog.

Early 20th century pilgrims to Split Rock, site in the north Bronx where Hutchinson was formerly believed to have died.

The earliest claim of Hutchinson dying at Split Rock was made in 1911, but I have been unable to determine the origins of that claim. The masque directed by Violet Oakley, with script and artifacts, is preserved at the New-York Historical Society, and provides a window into Hutchinson in the popular imagination; see The Book of the Words: Westchester County Historical Pageant, 1616-1846 (1909). Antiquarian Otto Hufeland makes a convincing case for Eastchester as the likely Hutchinson site in Anne Hutchinson’s Refuge in the Wilderness, and the Burning of the Village of White Plains (1929). From the instant of her death, commentators and historians debated the significance of Hutchinson’s legacy. Charles Francis Adams established the boilerplate with Antinomianism in the Colony of Massachusetts, 1636-1638 (1894). Adams’ work was updated by David D. Hall’s edition, The Antinomian Crisis, 1636-1638: A Documentary History (1968). At the center of Hall’s collection, which is now the definitive source, is A Short Story of the Rise, reigne, and ruinne of the Antinomians …. [1644], prepared by John Winthrop and Thomas Weld, which includes “The Examination of Mrs. Anne Hutchinson at the Court at Newtown.” Winthrop’s Journal (1996), which is available in abridged form in an edition prepared by Richard S. Dunn and Laetitia Yeandle, chronicles the Antinomian Crisis from the governor’s affair, and hints how other tensions (questions over the Bay Colony’s royal charter and the Pequod War) may have sharpened the tense proceedings. Hutchinson figures broadly in Edward Johnson’s Wonder Working Providence (1628-51), which defends the court, while Samuel Groome’s A Glass for the People of New-England (1676) blasts the intolerance shown towards Rhode Island Anabaptists, or Quakers.

Every aspect of the Antinomian Crisis has been covered in depth, with the exception of Hutchinson’s image in the popular and historical imagination. She never disappears entirely from history, yet her reputation seemed to rise in the last decade of the nineteenth century. Plymouth native John Vinson Adams defends Hutchinson’s accusers in The Antinomian Crisis of 1637 (1873). Charles Adams would collect the primary documents into Three Episodes in Massachusetts History (1892), while his son Brooks drafted her into a quirky analysis Boston’s liberation from dogma in The Emancipation of Massachusetts: The Dream and the Reality (1897). By the twentieth century Hutchinson appeared increasingly as a martyr for free speech, a point articulated in popular histories like Pauline Carrington Bouvé American Heroes and Heroines (1905), and one that gathered traction during the World War II years especially — see the campy yet gripping episode about Hutchinson of the radio series, You are There (1948). During periods of feminist ferment, she often appears as a model for later women. The 300-year anniversary of the Bay Colony brought three biographies of Hutchinson: Helen Augur’s novelistic An American Jezebel: The Life of Anne Hutchinson (1930); Edith Curtis’s Anne Hutchinson: A Biography (1930); and Unafraid: A Life of Anne Hutchinson (1930), by Winnifred King Rugg (who makes liberal use of exclamation points and claims Hutchinson as the founder of women’s clubs in America). The place as proto-feminist icon, where she speaks for a liberation that came later, prompted Edmund S. Morgan (Winthrop’s biographer, see below) to pen a grumpy corrective, setting the court within its time, in “The Case Against Anne Hutchinson” (1937). Reginald Pelham Bolton also penned A Woman Misunderstood as a corrective to the breathy accounts of Hutchinson’s end. As she had in the 1930s, Anne Hutchinson would speak to women in the 1970s, and she provides the subject for a compelling verse by the radical lesbian poet, Alta (1974)–among the many poetic tributes. A 2013 episode of the series Drunk History about Mary Dyer (directed by Jeremy Konner and starring Winona Ryder) pokes a stick at Puritan stodginess, but also mocks the moral tenor long associated with Hutchinson.

Emery Battis’ Saints and Sectaries: Anne Hutchinson and the Antinomian Crisis in the Massachusetts Bay Colony (1962) provides a detailed socio-economic context for the Antinomian Affair. Because the trial served as a test-case for the colony’s founding principles, a Hutchinson chapter appears to be requisite for any study of New England. Perry Miller drafts her case into a distinction between the covenants of grace and works in The New England Mind: The Seventeenth Century (1963); Morgan recognizes both the errors and the political needs of a church-state in The Puritan Dilemma: The Story of John Winthrop (1958). The next generation of scholars seemed to define their work against Miller noting the varieties of New England “minds.” Philip F. Gura emphasizes manifold dissent in A Glimpse of Sion’s Glory: Puritan Radicalism in New England, 1620-1660 (1984); Andrew Delbanco maintains that Puritan insecurities fed the Hutchinson trial in The Puritan Ordeal (1989). Being outside my field here, I miss several important works!

Anne Hutchinson is an “historiographical everywoman,” to quote Bryce Traister (below), and the scores of individual articles touch a variety of themes: language and theology; the Puritan socio-economic fabric; medicine (particularly in regards to Hutchinson’s miscarriage); politics of the individual and the state; and, of course, gender. Michael W. Kaufmann maps the critical tradition in “Post-secular Puritans: Recent Retrials of Anne Hutchinson” (2010). Patricia Caldwell examines the status of words in spiritual experience in her incisive “The Antinomian Language Controversy” (1976), while Michael G. Ditmore usefully unpacks political tensions through an exegetical reading in “A Prophetess in Her Own Country: An Exegesis of Anne Hutchinson’s Immediate Revelation” (2000). James F. Cooper, Jr. clarifies relations between church leaders and laity in “Anne Hutchinson and the ‘Lay Rebellion’ against the Clergy” (1988). Lad Tobin put gender as the “root cause” of the controversy in “A Radically Different Voice: Gender and Language in the Trails of Anne Hutchinson” (1990); Cheryl C. Smith casts Hutchinson as a feminist martyr in “Out of Her Place: Anne Hutchinson and the Dislocation of Power in New World Politics” (2006), while Bryce Traister asks (with emphasis on the historiographical tradition) how the controversy was about masculinity in “Anne Hutchinson’s ‘Monstruous Birth’ and the Feminization of Antinomianism” (1997). Based on the detailed description by John Winthrop, the “monster” that Hutchinson gave birth to in 1638 has been clinically diagnosed; see Margaret V. Richardson and Arthur T. Herrig, “New England’s First Recorded Hydatidiform Mole,” New England Journal of Medicine (1957), as well as Battis’ appendix to Saints and Sectaries which explains Hutchinson’s temper as menopausal instability. Anne Jacobson Schutte provides an impressive contextualization of the birth in seventeenth century medicine and cosmology; see “‘Such Monstruous Births’: A Neglected Aspect of the Antinomian Controversy” (1985). In the 1990s, when I was in graduate school, the Antimonian Crisis served as a touchstone for debates about ideology, freedom and gender identity in the New American studies; see, for example, the dissertations by James Francis Egan (1991), Sarah Elizabeth Chinn (1996) and Elizabeth Maddock Dillon (1995), and finally Michelle Burnham’s effort crisis to situate New England within the field in “Anne Hutchinson and the Economics of Antinomian Selfhood in Colonial New England” (1997).

The scholarly literature on Ralph Waldo Emerson is equally insurmountable. A web search of his name yields almost 8 million hits; this figure puts him well behind William Shakespeare (23 million), above John Milton (3 million) and just slightly below Ludwig van Beethoven (10 million). For his publications Emerson famously mined his journals, and through the use of definitive editions, scholars routinely read the private and published work in conversation. Traces of “Self-Reliance,” for example, appear in The Early Lectures (edited by Stephen Whicher and Robert E. Spiller), and in the Journals and Miscellaneous Notebooks (edited by William H. Gilman and several others). The Letters of Ralph Emerson (ed. Ralph L. Rusk) provide further insight into the essays, though by the author’s own admission, he was not born under an “epistolary star.”

I have relied heavily on anthologies of criticism (of which there are many) to get a handle on the amount of criticism that can overwhelm even the most diligent Emersonians. Milton R. Konvitz and Stephen E. Whicher’s Emerson: A Collection of Critical Essays (1962), the first of its kind, samples writing to that date and provides insight into the author’s mid-century recovery; Ralph Waldo Emerson: A Collection of Critical Essays (1993), edited by Lawrence Buell, is the bookend to Konvitz and Whicher. Concise historical-biographical essays in A Historical Guide to Ralph Waldo Emerson (2000), edited by Joel Myerson, situate the author firmly in the nineteenth century. For the sheer range of material, valuable for reasons of brevity, see the Norton Critical Edition, prepared by Joel Porte and Saundra Morris, The Cambridge Companion to Ralph Waldo Emerson (1999). These anthologies, taken together, allow us to follow trajectory from influence and admiration; to canonization and critique, often backhanded, in the Victorian period; an appreciation of American qualities author in the early twentieth century, a burst of scholarship in the 1950s–which continues and which now emphasizes trans-Atlantic crossings.

With particular attention to “Self-Reliance,” Joel Porte shows how the critical tradition serves as a kind of distraction in “The Problem of Emerson” (1973). O.W. Firkins provides a memorable challenge to Emersonian optimism in “Has Emerson a Future?” (1933), while Stephen E. Whicher emphasizes a dialect of optimism and doubt in his landmark Freedom and Fate: An Inner Life of Ralph Waldo Emerson (1953). Wesley T. Mott reviews theological positions, with connections to Puritanism, in “Emerson and Antinomianism: The Legacy of the Sermons” (1978); Mott also clarifies shades of individualism in “‘The Age of the First Person Singular’: Emerson and Individualism” (2000). With rightful apprehension, I have let my connections of Puritanism and Emerson be guided by Perry Miller’s speculative, “From Edwards to Emerson” (1940); while this connection has been challenged, even derided, I would note that my interests remain with Emerson and Hutchinson as they were read at mid-century.

Commentators debate and unravel the commercial implications of Emersonian thought; see Michael T. Gilmore “Emerson and the Persistence of Commodity” (1982); and intriguing connections to trust law made by Howard Horwitz in By the Law of Nature: Form and Value in Nineteenth-Century America (1991). Given the extent of writing, with that in mind, I should note what I overlook. I do not grapple with the philosophical tradition that runs John Dewey, to Richard Rorty and Stanley Cavell, to Cornel West. Nor do I grapple with discussions of Emerson and the “national symbolic,” particularly in the 1990s, as leading Americanists such as Sacvan Bercovitch (“Emerson, Individualism, and Liberal Dissent from his 1993 book The Rites of Assent: Transformations of the Symbolic Construction of America to Donald E. Pease, “‘Experience, Antislavery, and the Crisis of Emersonianism” (2007). I’m sure there’s more I have missed … which is my point, that the writing about Ralph Waldo Emerson is endless.

Works Cited

__________ . Report of the Westchester County Park Commission for the Acquisition of Parks, Parkways or Roads. White Plains [?]: Westchester County Parks Commission, 1923.

Ace, Goodman. You Are There: Ann [sic] Hutchinson’s Trial. Episode 43. New York, Columbia Broadcasting System (Sept. 26, 1948). Accessed on YouTube on November 24, 2020.

Adams, Brooks. The Emancipation of Massachusetts: The Dream and the Reality. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1916.

Adams, Charles Francis. Antinomianism in the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, 1636-1638, including the Short Story and Other Documents. Boston: Prince Society, 1894.

__________ . Three Episodes of Massachusetts History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1892.

Adams, John Vinton. The Antinomian Crisis of 1637. Boston, 1873.

Alta. “The Vow/for Anne Hutchinson. San Leandro, CA.: Shameless Hussy Press, 1974.

Augur, Helen. An American Jezebel: The Life of Anne Hutchinson. New York: Brentanos, 1930.

Barr, Lockwood. A brief, but most complete & true Account of the Settlement of the Ancient Town of Pelham, Westchester County, State of New York. Richmond, Va.: Dietz Press, 1946.

Battis, Emery John. Saints and Sectaries: Anne Hutchinson and the Antinomian Crisis in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1962.

Bercovitch, Sacvan. The Rites of Assent: Transformations of the Symbolic Construction of America. New York: Routledge, 1993.

Bolton, Reginald Pelham. “Anne Hutchinson’s Memorial.” New York Times (14 March 1922).

__________ . “The Home of Mistress Ann[e] Hutchinson at Pelham, 1642-43.” The New-York Historical Society Quarterly 6, no. 2 (July 1922): 43-52.

__________ . A Woman Misunderstood. New York: Schoen, 1931.

Bouvé, Pauline Carrington Rust. American Heroes and Heroines. Boston: Lothrop, 1905.

Buell, Lawrence, ed. Ralph Waldo Emerson: A Collection of Critical Essays. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1993.

Burnham, Michelle. “Anne Hutchinson and the Economics of Antinomian Selfhood in Colonial New England.” Criticism 39, no. 3 (Summer 1997): 337-58.

Caldwell, Patricia. “The Antinomian Language Controversy.” Harvard Theological Review 69, no. 3/4 (July-Oct. 1976): 345-67.

Chinn, Sarah Elizabeth. ‘Much Madness is Divinest Sense’: Heresy as a Trajectory in American Women’s Writing from Anne Hutchinson to Gertrude Stein. Ph.D. Dissertation Columbia University (1996).

Cooper, James F., Jr. “Anne Hutchinson and the ‘Lay Rebellion’ against the Clergy. The New England Quarterly 61, no. 3 (Sept. 1988): 381-97.

Curtis, Edith [Roelker]. Anne Hutchinson: A Biography. Cambridge: Washburn & Thomas, 1930.

Dillon, Elizabeth Maddock. Representing the Subject of Freedom: Liberalism, Hysteria, and Dispossessive Individualism. Ph.D. Dissertation University of California, Berkeley. 1995.

Ditmore, Michael. “A Prophetess in Her Own Country: An Exegesis of Anne Hutchinson’s ‘Immediate Revelation.'” The William & Mary Quarterly 57, no. 2 (2000): 349-92.

Egan, James Francis. Ideology and the Study of American Culture: Early New England Writing and the Idea of Experience. Ph.D. Dissertation University of California Santa Barbara (Aug. 1991).

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. The Complete Essays and Other Writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson. Edited by Brooks Atkinson. New York: Modern Library, 1950.

__________ . The Early Lectures. Ed. Stephen E. Whicher and Robert E. Spiller. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1959-.

__________ . Emerson’s Prose and Poetry. Ed. Joel Porte and Saundra Morris. New York: Norton, 2001.

__________. Journals and Miscellaneous Notebooks, ed. William H. Gilman, et al. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1960-82.

_________ . The Letters of Ralph Waldo Emerson. Edited by Ralph L. Rusk. New York: Columbia University Press, 1939.

Firkins, Oscar W. “Has Emerson a Future?” Selected Essays of O.W. Firkins. Minneapolis: U Minnesota P, 1933. 79-93. Reprinted in Emerson’s Poetry and Prose, edited by Joel Porte and Saundra Morris, 638-63. New York: Norton, 2001.

Gilmore, Michael T. “Emerson and the Persistence of Commodity.” In Emerson: Prospect and Retrospect, edited by Joel Porte, 76-85. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1982.

Groome[s]. Samuel. A Glass for the People of New England …. London, 1676.

Gura, Philip. A Glimpse of Sion’s Glory: Puritan Radicalism in New England. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1984.

Hall, David D., ed. The Antinomian Crisis, 1636-1638: A Documentary History, 1636-38. Middletown, Ct..: Wesleyan University Press, 1988.

Horwitz, Howard. By the Law of Nature: Form and Value in Nineteenth-Century America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Hufeland, Otto. Anne Hutchinson’s Refuge in the Wilderness, and the Burning of the Village of White Plains. Binghamton, N.Y.: Vail-Ballou Press, 1929.

Jackson, Kenneth. Crabgrass Frontier: Suburbanization of America. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Johnson, Edward. Johnson’s Wonder-Working Providence, 1628-1651. [The Wonder-Working Providence of Sion’s Savior in New-England.] Edited by J. Franklin Jameson. New York: Scribners, 1910.

Kaufman, Michael W. “Post-Secular Puritans: Recent Retrials of Anne Hutchinson.” Early American Literature 45, no. 1 (2010): 31-59.

Konner, Jeremy, dir. Drunk History: Boston (season 1, episode 4). New York; Comedy Central, 2013. Clip accessed November, 21, 2020.

Konvitz, Milton R. and Stephen E. Whicher (eds.). Emerson: A Collection of Critical Essays. Englewood-Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1962.

Miller, Perry. “From Edwards to Emerson” [1940]. Nature’s Nation. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1967.

__________ . The New England Mind: The Seventeenth Century. New York: Macmillan, 1939.

Morgan, Edmund S. “The Case Against Anne Hutchinson.” New England Quarterly 10, no. 4 (Dec. 1937): 635-49.

__________ . The Puritan Dilemma: The Story of John Winthrop. Boston: Little, Brown, 1958.

Mott, Wesley T. “‘The Age of the First Person Singular’: Emerson and Individualism.” In A Historical Guide to Ralph Waldo Emerson, edited by Joel Myerson, 61-100. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

__________ . “Emerson and Antinomianism: The Legacy of the Sermons.” American Literature 50, no. 3 (Nov. 1978): 368-97.

Myerson, Joel, ed. A Historical Guide to Ralph Waldo Emerson. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Oakley, Violet. The Book of the Words: Westchester County Historical Pageant, 1616-1846. Philadelphia (?): n.p., 1909.

Pease, Donald E. “‘Experience,’ Antislavery and the Crisis of Emersonianism.” boundary 2 34, no. 2 (2007): 71-103.

Porte, Joel. “The Problem of Emerson.” Uses of Literature. Harvard English Studies 4, edited by Monroe Engel (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1973): 85-114. Reprinted in Emerson’s Poetry and Prose, edited by Joel Porte and Saundra Morris, 679-97. New York: Norton, 2001.

Porte, Joel and Saundra Morris, eds. The Cambridge Companion to Ralph Waldo Emerson. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Richardson, Margaret and Arthur T. Hertig. “New England’s First Recorded Hydatidiform Mole.” New England Journal of Medicine 207, no. 11 (March 1959): 544-45.

Rugg, Winnifred, King. Unafraid: A Life of Anne Hutchinson. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1930.

Schutte, Anne Jacobson. “‘Such Monstruous Births’: A Neglected Aspect of the Antinomian Controversy.” Renaissance Quarterly 38, no. 1 (Spring 1985): 85-106.

Smith, Cheryl C. “Out of Her Place: Anne Hutchins on and the Dislocation of Power in New World Politics.” Journal of American Culture 29, no. 4 (Dec. 2006): 437-53.

Tobin, Lad. “A Radically Different Voice: Gender and Language in the Trails of Anne Hutchinson.” Early American Literature 25, no. 3 (1990): 253-70.

Traister, Bryce. “Anne Hutchinson’s ‘Monstruous Birth’ and the Feminization of Antinomianism.” Canadian Review of American Studies 27, no. 2 (1997): 138-58.

Whicher, Stephen E. Freedom and Fate: An Inner Life of Ralph Waldo Emerson. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1953.

Winthrop, John. The Journal of John Winthrop, 1630-1649. Edited by Richard S. Dunn and Laetitia Yeandle. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996.

__________ . A Short Story of the Rise, Reigne, and Ruine of the Antinomians, Familists & Libertines, that infected the Churches of New England [1644]. Reprinted The Antinomian Controversy, 1636-38, edited by David D. Hall, 199-310. Middletown, Ct..: Wesleyan University Press, 1988.