The 1803 uprising at Igbo Landing has long served as a shorthand for the psychic burden of slavery, and in the painful context of the Middle Passage, as a point of negotiation between documentation and memory. My research started with a remarkable essay by Timothy Powell, who compares oral, written and literary narratives to address the status of evidence in humanities scholarship; see “Summoning the Ancestors: The Flying Africans’ Story and Its Enduring Legacy” (2010). Powell presents a distilled version of this argument, shifting problematically from speculative to documentary mode, in the Ebos Landing entry of The Georgia Encyclopedia.

Accounts of the Dunbar Creek episode come from documentary, oral and local (or antiquarian) sources. Initial written reports survive in letters, now at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (Butler Family Papers). Malcolm Bell, Jr. cites these letters, plus oral traditions noted below, in Major Butler’s Legacy: Five Generations of a Slave Holding Family (1987). The uprising had immediate notoriety, as an 1857 letter from Anna Matilda Page King indicates; see Anna: The Letters of a St. Simons Island Plantation Mistress, 1817-1859 (2002). The Georgia Writers Project, Drums and Shadows: Survival Studies among Georgia’s Coastal Negroes (1940, 1986) serves as the primary record for oral traditions, although accounts within this collection vary more widely than commentators have recognized. On the local front, finally, historian and postmistress Margaret Davis Cate consolidated the Igbo Landing tradition, through a series of publications that include Our Todays and Yesterdays: A Story of Brunswick and the Coastal Islands (1926, 1930), Pilgrimage to Historic St. Simons Island (1929), and her popular illustrated history, Early Days of Coastal Georgia (1955); Cate’s papers, at the Hargrett Library at the University of Georgia, provide a trove of information about St. Simons, early tourism there, and the efforts of an indefatigable, unaffiliated female historian. A second widely-cited source is H.A. Sieber, whose typescript accounts “The Igbo Stroke of 1803: Rebellion and Freedom March at Ebo Landing” (1988) and “The Factual Basis of the Ebo Landing Legend” are at the Coastal Georgia Historical Society. Sieber’s reviews of oral and popular traditions have seeped into government documents (Ciucevich, below), press releases and an Igbo Landing Wikipedia page.

At a broader level, Igbo Landing provides a case study of local fascination and institutional neglect. A quick scan of Georgia histories from the past century will yield little mention. In local histories, however, and in the many celebrations of St. Simons’ natural beauty and lore, Igbo Landing gets the cursory paragraph or two. Abbie Fuller Graham’s scrapbook, Old Mill Days: St. Simons Mills, Georgia, 1874-1908 (1976), reprints periodical clippings. Lydia Parrish’s Slave Songs of the Georgia Sea Islands (1942) includes a second-hand telling, in which the slaves walk into the water (rather than fly). And the Federal Writers Project, Georgia: The WPA Guide to Its Town and Countryside (1940) marks Dunbar Creek as a haunted site, with the Igbos committing mass suicide under a “Chief Ebo.”

In the accounts for general readers, the 1803 episode is cast in one of three ways: within a narrative of Civil Rights or social justice; as the dark chapter in the longer history of a beautiful place; or as a ghost story that tropes the “local.” Historian Benjamin Allen includes images of the HSP letters to establish a starting point for racial uplift in Glynn County, Georgia: Black America Series (2003), while oral histories in Stephen Doster (ed.), Voices from St. Simons: Personal Narratives of an Island’s Past (2008) cite Igbo Landing as a marker of continued hurt. Caroline Couper Lovell contrasts the bitter 1803 episode against nostalgia in The Golden Isles of Georgia (1932). Jingle Davis’ sumptuous Island Time: An Illustrated History of St. Simons Island (2013) couches the ghost story against historical documentation. Craig Dominy spins the character of “Chief Ebo,” first mentioned in the WPA Guide, into “Oba,” with a full-blown African backstory; this version circulates widely on Dominy’s internet anthology, The Moonlit Road (1998). Other versions include Burnette (Lighthle) Vanstory, Ghost Stories and Superstitions of Old Saint Simons (1970), and Robert C. Hatchell, St. Simons (1983). Popular author Eugenia Price incorporated Igbo Landing into her St. Simons trilogy; for a guide of the island through the novelist’s eyes, see Mary Bray Wheeler, Eugenia Price’s South: A Guide to the People and Places of her Beloved Region (1993). In this light Sophia Nahli Allison’s short film, “Dreaming Gave Us Wings,” feels like a correcting, looking to an ancestral past for future flight.

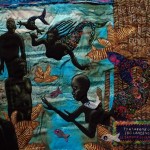

Spiraling outward, Igbo Landing serves as a site-specific-yet-universal metaphor for resistance and recovery across the black diaspora. Marquetta Goodwine (Queen Quet) uses the story to frame a story of preservation and cultural continuity in her edited collection, The Legacy of Ibo Landing: Gullah Roots of African American Culture (2002). Activists with the Ebo (Igbo) Landing Project, in a similar vein, go through St. Simons to reconnect with Africa. Artists have memorialized Igbo Landing across media: Laura R. Gadson through a quilt, “Reception at Ibo Landing” (2012); painting by Dee Williams, “The Legend of Ebo Landing” (2010?); dramatic performance by Alva Rogers, “The Story of Ibo Landing“; drawings by Donovan Nelson, “Ibo Landing” (2011?); poetry by Honorée Fannone Jeffers, including “Naming Ceremony” (2015); an historical ballad by Margaret McGarvey, “The Ballad of Ebo” (1964); symphonic jazz by Wendell Logan, “Ibo Landing” (1985); in Julie Dash’s film, Daughters of the Dust (1991); and most significantly in Paule Marshall’s quest novel, Praisesong for the Widow (1984).

Spiraling outward, Igbo Landing serves as a site-specific-yet-universal metaphor for resistance and recovery across the black diaspora. Marquetta Goodwine (Queen Quet) uses the story to frame a story of preservation and cultural continuity in her edited collection, The Legacy of Ibo Landing: Gullah Roots of African American Culture (2002). Activists with the Ebo (Igbo) Landing Project, in a similar vein, go through St. Simons to reconnect with Africa. Artists have memorialized Igbo Landing across media: Laura R. Gadson through a quilt, “Reception at Ibo Landing” (2012); painting by Dee Williams, “The Legend of Ebo Landing” (2010?); dramatic performance by Alva Rogers, “The Story of Ibo Landing“; drawings by Donovan Nelson, “Ibo Landing” (2011?); poetry by Honorée Fannone Jeffers, including “Naming Ceremony” (2015); an historical ballad by Margaret McGarvey, “The Ballad of Ebo” (1964); symphonic jazz by Wendell Logan, “Ibo Landing” (1985); in Julie Dash’s film, Daughters of the Dust (1991); and most significantly in Paule Marshall’s quest novel, Praisesong for the Widow (1984).

The story of the Flying African, while sometimes claimed to have its origins at Dunbar Creek, spans the African diaspora. The ubiquitous Flying African appears in Caribbean texts, including Norman Paul’s autobiography, Dark Pilgrim: The Life and Work of Norman Paul (1963); Michelle Cliff’s novel Abeng (1984); Earl Lovelace’s novel, Salt (1996); Esteban Montejo’s Autobiography of a Runaway Slave (1968); a short volume of children’s stories, Legends of Suriname, told by Petronella Breinburg (1971); and Tomás Gutiérrez Alea’s film, La Última Cena (1976). Monica Schuler cites contemporary stories from Jamaica in ‘Alas, Alas Kongo’: A Social History of Indentured African Immigration into Africa (1980), while the African poet Kofi Awwonor links water and flight in “On the Gallows Once” (2014). Examples from the U.S. South include J.D. Suggs’ “The Flying Man”; Richard M. Dorston’s American Negro Folktales (1956); Julius Lester’s “People Who Could Fly” Black Folktales (1969); and a retold version in Bucklin Moon’s felicitously entitled Primer for White Folks (1945). Virginia Hamilton incorporated the legend into a popular illustrated children’s book, The People Could Fly: American Black Folktales (1985). Aleshea Harris recently adapted the motif for stage in Rip.Tied. (2012). Since the publication of Song of Solomon (1977), finally, the story has gravitated around Toni Morrison.

Historical studies emphasize African roots and cosmology. St. Clair Drake singles out the return as a Pan-African theme in “Diaspora Studies and Pan-Africanism” (1982). Michael Gomez describes the West African context to Igbo resistance (suicides, escapes and folklore) in Exchanging our Country Marks: The Transformation of African Identities in the Colonial and Antebellum South (1998). Terri L. Snyder explains “suicide ecology,” the social factors behind the decision to take one’s own life, in “Suicide, Slavery, and Memory in North America” (2010). Mary Karasch connects strategies of black resistance and escape to water in Slave Life in Rio de Janeiro, 1808-1850 (1987). Wyatt MacGaffey maps the African physical and spirit worlds, and the role of water as a boundary, or Kalenga, in “The West in Congolese Experience” (1972).

Americanist literary scholarship has focused on Praisesong for the Widow and Song of Solomon, novels that spin myth into fiction but meditate in important ways on the significance of that myth. Morrison discusses the flying African and her readings in Drums and Shadows in a short video sponsored by the National Visionary Leadership Project. Gay Wilentz takes a Jungian approach, linking folklore and fiction, to suggest that flight symbolizes the need for transcendence, in “If You Surrender to the Air: Folk Legends of Flight and Resistance in African American Literature” (1989-90). Wendy Walters maintains that the two novels establish a counternarrative to slavery in “‘One of Dese Mornings, Bright and Fair,/Take My Wings and Cleave De Air’: The Legend of the Flying African and Diasporic Consciousness” (1997). Lorna McDaniels notes how figures of flight expresses a desire for freedom, and unspoken accession to suicide, in “The Flying Africans: Extent and Strength of the Myth in the Americas” (1990); for specific reference to Paule Marshall, see also The Big Drum Ritual of Carriacou: Praise Songs in Rememory of Flight (1998). Angelita Reyes (who generously commented on an MLA paper I presented) connects literary and African sources in anthropology, showing how the story negotiated the taboo of suicide in Mothering across Cultures: Postcolonial Representations (2012). Rebecca Schneider attends to liminality in the many stories in “This Shoal Which Is Not One: Island Studies, Performance Studies, and Africans Who Fly” (2020).

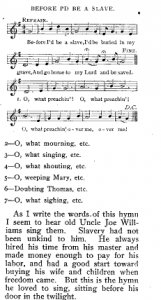

The folding of “Oh Freedom” into Igbo Landing occurs in recent more versions, and raises questions about chronology and memory in African culture. The song does not appear in the earliest published anthology of African-American music from the lowcountry, Slave Songs of the United States (1867), assembled by William Francis Allen, Charles Pickard Ware, and Lucy McKim Garrison. William E. Barton provides the first published record, after Reconstruction, in “Hymns of the Slave and Freedman,” New England Magazine (1899). Henry Edward Krehbiel maintained that “Oh Freedom” conflated two white tunes in Afro-American Folksongs: A Study in Racial and National Music (1913), a perspective challenged by liberation theologian James H. Cone, who uses “Oh Freedom” to establish terms of critique that begins from African-American experience in The Spirituals and the Blues: An Interpretation (1972) and in God of the Oppressed (1975). Following Cone, theomusicologist John Michael Spencer reads hymns like “Oh Freedom” transhistorically; see Protest and Praise: Sacred Music of Black Religion (1990), and Re-Searching Black Music (1996). The storyteller Zyangquelyn A. Witherspoon (“Auntie Zya”) compellingly connects “Oh Freedom” to Ibgo Landing in her video “Out of the Past: The Ibo Landing Story” (2013).

The folding of “Oh Freedom” into Igbo Landing occurs in recent more versions, and raises questions about chronology and memory in African culture. The song does not appear in the earliest published anthology of African-American music from the lowcountry, Slave Songs of the United States (1867), assembled by William Francis Allen, Charles Pickard Ware, and Lucy McKim Garrison. William E. Barton provides the first published record, after Reconstruction, in “Hymns of the Slave and Freedman,” New England Magazine (1899). Henry Edward Krehbiel maintained that “Oh Freedom” conflated two white tunes in Afro-American Folksongs: A Study in Racial and National Music (1913), a perspective challenged by liberation theologian James H. Cone, who uses “Oh Freedom” to establish terms of critique that begins from African-American experience in The Spirituals and the Blues: An Interpretation (1972) and in God of the Oppressed (1975). Following Cone, theomusicologist John Michael Spencer reads hymns like “Oh Freedom” transhistorically; see Protest and Praise: Sacred Music of Black Religion (1990), and Re-Searching Black Music (1996). The storyteller Zyangquelyn A. Witherspoon (“Auntie Zya”) compellingly connects “Oh Freedom” to Ibgo Landing in her video “Out of the Past: The Ibo Landing Story” (2013).

The compression of “Oh Freedom” onto Igbo Landing evidences how traditional hymns were incorporated during the Civil Rights Movement, as part of a much longer narrative of resistance and liberation; see Robert Darden, Nothing but Love in God’s Water: Black Sacred Music from the Civil War to the Civil Rights Movement (2014). For more general reviews of the spirituals, see Mellonnee Burnin’s textbook survey, “Religious Music” in African American Music: An Introduction (1996); see also Dena J. Epstein’s Sinful Tunes and Spirituals: Black Folk Music to the Civil War (1977, 2003), which painstakingly reconstructs African-American musical culture from outside accounts. On black music and chronology, see John Cruz and the “sedimented history” in Culture on the Margins: The Black Spiritual and the Rise of American Cultural Interpretation (1999); Joan Dayan makes a similar case in her influential literary study of voodoo, Haiti, History, and the Gods (1995), emphasizing how “encrustrations” in Caribbean history require a different sense of temporality. Many of the questions raised by Igbo Landing, notably memory and the status of text, resonate with scholarship in musicology. Ronald Radano’s revisionist Lying Up a Nation: Race and Black Music (2003) complicates ideas of the “transhistorical” text, noting the difficulty of essentializing when one reads without notation, while Cheryll A. Kirk-Duggan emphasizes transcendent curative powers for hymns like “Oh Freedom” in Exorcising Evil: A Womanist Perspective on the Spirituals (1997).

Despite the prominence of Igbo Landing in culture and memory, the scholarship has focused more on what happened than strategies of representation. In my own research, I benefited greatly from personal interviews and exchanges, including: Douglas Chambers, University of Southern Mississippi, with whom I have sought to clarify the work of historical and literary study; Mimi Rogers of the Coastal Georgia Historical Society; the St. Simons African American Heritage Coalition, including Amy Roberts, who gave me a tour the island that included a visit to Igbo Landing, and Chip Wilson, who offered me a musical rendition of “Oh Freedom” when I asked about the 1803 uprising; Huntley Allen, who is deeply vested in preserving the legacy of Igbo Landing; Susan Durkes, with the McIntosh County Shouters; Jane Aldrich, with Lowcountry Heritage Education; and Braima Moiwai, who helped me understand American-African connections. This offering, in the form of a scholarly review, intends to honor the role of historical memory in coming to grips with a painful chapter from our shared past.

Note: The legacy of the Flying African is ongoing, and new sources continue to appear since this page was prepared in 2018. “The lives of the ancestors live on in many stories that have never been written, only passed on by tellin'” (Zyangquelyn ‘Auntie Zya’ Witherspoon).

Works Referenced

Allen, Benjamin. Glynn County, Georgia: Black America Series. Charleston, S.C.: Arcadia, 2003.

Allison, Sophia Nahli. “Dreaming Gave Us Wings.” The New Yorker (March 7. 2019). Accessed Jan. 27, 2021.

[Associated Press]. “Slave Legend draws people for two-day remembrance in coastal Georgia” (Sept. 2, 2002).

Awoonor, Kofi. “On the Gallows Once.” In The Promise of Hope: New and Selected Poems. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2104. Available at Academy of American Poets, accessed Sept. 2, 2020.

Bell, Malcolm, Jr. Major Butler’s Legacy: Five Generations of a Slaveholding Family. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1987.

Berlin, Jacqueline. “Researcher has new version of legend.” The Brunswick News, Aug. 8, 2003.

Bracy, Ihsan. Ibo Landing. New York: Cool Grove, 1998.

Breinburg, Petronella. Legends of Suriname. London: New Beacon, 1971.

Cate, Margaret Davis. Early Days of Coastal Georgia. St. Simons Island, Ga.: Fort Federica Association, 1955

_________ . Our Todays and Yesterdays: A Story of Brunswick and the Coastal Islands. Brunswick, Ga.: Glover, 1926, 1930. Reproduced at Coastal Georgia Genealogy and History, accessed on Sept. 1, 2020.

_________ . A Pilgrimage to Historic St. Simons Island. Brunswick: Daughters of the American Revolution, 1929.

__________ . Papers. Hargrett Library, University of Georgia.

Ciucevich, Robert A. Glynn County Historic Resources Survey Report. Savannah, GA: Quatrefoil Historical Preservation Consulting, 2009.

Cliff, Michelle. Abeng. New York: Dutton, 1984.

Conyeani. “Of Igbo Slave Rebellion at ‘Igbo Landing, Georgia, and Igbo Jewish Identity.” African Sun Times, June 5, 2013.

Dominey, Craig. “Ibo Landing.” www.themoonlitroad.com, accessed, Sept 2, 2020.

Dorson, Richard M., ed. American Negro Folktales. Greenwich, CT: Fawcett, 1956.

Doster, Stephen, ed. Voices from St. Simons: Personal Narratives of an Island’s Past. Winston-Salem, N.C.: John F. Blair Publisher, 2008.

Drake, St. Clair. “Diaspora Studies and Pan-Africanism.” In Global Dimensions of the African Diaspora, edited by Joseph E. Harris, 341-402. Washington, D.C.: Howard University Press, 1982.

Elia, Nada. “‘Kum Buba Yali Kummm Buba Tambe, Ameen, Ameen, Ameen’: Did Some of the Flying Africans Bow to Allah?” Callaloo 26, no. 1 (2003): 182-202.

[Georgia Writers’ Project, Savannah Unit.] Drums and Shadows: Survival Studies among the Georgia Coastal Negros. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1986.

[Glynn County, Ga.] “Ebo Landing.” glynncounty.com, accessed Sept. 2, 2020.

Gomez, Michael. Exchanging our Country Marks: The Transformation of African Identities in the Colonial and Antebellum South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998.

Graham, Abbie Fuller. Old Mill Days. St. Simons, GA.: St. Simons Public Library, 1976.

Greene, Sandra. “Whispers and Silences: Explorations in African Oral History.” Africa Today 50, no. 2 (Fall/Winter 2003): 41-53.

Gutiérrez Alea, Tomás (dir). La Última Cena. 1976; Havana: Instituto Cubano del Arte Industria Cinematográficos.

Hamilton, Virginia. The People Could Fly: American Black Folktales. New York: Knopf, 1985.

Hatchell, Robert C. St. Simons. St. Simons: Sojourn Publications, 1983.

Hendries, Deborah. “Ebo Landing”/”The Legend of Ebo Landing.” Coastal Center for the Arts, 2010, accessed on YouTube Sept. 2, 2020.

Hull, Barbara. St. Simon’s Enchanted Island: A History of the Most Historic of Georgia’s Fabled Golden Isles. Atlanta: Cherokee Publishing Co., 1980.

Jeffers, Honorée Fannone. “Naming Ceremony.” Available at Academy of American Poets, accessed Sept. 2, 2020.

Karasch, Mary C. Slave Life in Rio de Janeiro, 1808-1850. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1987.

King, Anna Matilda. Anna: The Selected Letters of a Sea-Island Plantation Mistress, 1817-59, edited by Melanie Pavich. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2002.

Lester, Julius. “People Who Could Fly.” In Black Folktales, 147-52. New York: Grove Press, 1969.

Logan, Wendell. “Ibo Landing: for Orchestra” [jazz symphony]. Oberlin, Oh.: Oberlin Conservatory, 1985.

Lovell, Caroline Couper. The Golden Isles of Georgia. Boston: Little, Brown, 1933.

__________ . The Light of Other Days. Macon: Mercer University Press, 1995.

Lovelace, Earl. Salt. New York: Persea, 2004.

MacGaffey, Wyatt. “The West in Congolese Experience.” In Africa and the West, edited by Philip D. Curtin, 49-74. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1972.

Marshall, Paule. Praisesong for the Widow. New York: Plume, 1984.

McDaniel, Lorna. The Big Drum Ritual of Carriacou: Praise Songs in Rememory of Flight. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 1998.

__________ . “The Flying Africans: Extent and Strength of the Myth in the Americas.” New West Indian Guide/Nieuwe West-Indische Gids 64, no. 122 (1990): 28-40.

McFeely, William S. Sapelo’s People: A Long Walk into Freedom. New York: Norton, 1994.

McGarvey, Margaret. D*Dawn, and Other Poems. Darien: Ashantilly Press, 1964.

Montejo, Esteban. The Autobiography of a Runaway Slave. New York: Pantheon, 1968.

Moon, Bucklin, ed. Primer for White Folks. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran and Co., 1945.

Moreno Fraginals, Manuel. El Ingenio: complejo económico social cubano de azúcar. Habana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, 1978.

[National Visionary Leadership Project]. “Toni Morrison with the Visionary Project: ‘Song of Solomon.” Accessed on YouTube, Sept. 2, 2020.

Paul, Norman. Dark Pilgrim: The Life and Work of Norman Paul, edited by M.G. Smith. Kingston: University of the West Indies, 1963.

Ponmier Taquechel, María. “El Suicidio esclava en Cuba en los Años 1840.” Anuario de Estudios Americanos 43. Sevilla (1986): 69-86.

Powell, Timothy. “Ebos Landing.” New Georgia Encyclopedia, accessed on Sept. 2, 2020.

__________ . “Summoning the Ancestors: The Flying Africans’ Story and Its Enduring Legacy.” In African American Life in the Georgia Lowcountry, edited by Philip Morgan, 253-80. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2010.

Reyes, Angelita. Mothering across Cultures: Postcolonial Representations. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012.

Schneider, Rebecca. “This Shoal Which is Not One: Island Studies, Performance Studies, and Africans Who Fly.” Island Studies Journal 15, no. 2 (2020): 201-218. Accessed Jan. 27, 2021.

Schuler, Monica. ‘Alas, Alas Kongo’ A Social History of Indentured African Immigration into Africa. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980.

Schuler, Monica. ‘Alas, Alas Kongo’ A Social History of Indentured African Immigration into Africa. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980.

Sieber, H.A. The Factual Basis of the Ebo Landing Legend. St. Simons Island: Coastal Georgia Historical Society [unpublished manuscript on deposit].

Snyder, Terri L. “Suicide, Slavery, and Memory in North America.” The Journal of American History 97, no. 1 (June 2010): 39-62.

Walters, Wendy. “One of Dese Mornings, Bright and Fair/Take My Wings and Cleave the Air’ The Legend of the Flying African and Diasporic Consciousness.” MELUS 22, no. 3 (Fall 1997): 3-29.

Wheeler, Mary Bray. Eugenia Price’s South: A Guide to the People and Places of her Beloved Region. Atlanta: Longstreet Press, 1993.

Wightman, Orrin Sage and Margaret Davis Cate. Early Days of Coastal Georgia. St. Simons Island: Fort Federica Association, 1955.

[Wikipedia]. “Igbo Landing.” wikipedia.org, accessed on Sept. 2, 2020.

Wilentz, Gay. “If You Surrender to the Air: Folk Legends of Flight and Resistance in African American Literature.” MELUS 16, no. 1 (Spring 1989-90): 21-32.

Witherspoon, Zyangquelyn A. “The Igbo Landing Story.” DKG Fine Arts Gallery, accessed Sept. 5, 2020.