Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca spent eight years in America but the long textual and scholarly journey of his life continues. Three surviving members of the Narváez expedition, including Cabeza de Vaca, filed a “Joint Report” upon their return to Mexico in 1536-37, and the first published account appeared in Gonzalo Fernández de Oveido y Valdéz’s encyclopedic General and Natural History of the Indies (1535). A partial translation of Ovideo, with a focus on Texas, appears in Harbert Davenport (ed.), “The Expedition of Pánfilo de Narváez” (1924). Upon returning to Spain, Cabeza de Vaca published La relación que dio Álvar Nuñez Cabeça de Vaca de lo acaescido en las Indias en la armada donde iva por governador Pánphilo de Narbáez, desde el año de veinte y siete hasta el año de treinta y seis que bolvió a Sevillas con tres de su compañía (Zamora, 1542), reprinted in Adorno and Pautz (1999); a second edition appeared in Vallodolid in 1555. The story of the journey is many titled, though from the eighteenth to the twentieth century, it has been called the Naufragios, or shipwrecks (when students misidentify the title on quizzes today, I feel guilty taking off points).

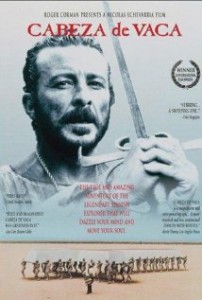

Notably, an English translation did not appear until 1851, by Thomas Buckingham Smith, after the Mexican War. Buckingham Smith was followed by Fanny Bandelier (1904), which stood for years as the standard, until Martín A. Favata and José B. Fernández’ Account (1993). The definitive is now the bilingual, three-volume Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca: His Account, His Life, and the Expedition of Pánfilo de Narvaez, by Rolena Adorno and Patrick Charles Pautz (1999), with a condensed version available in paperback (2003). Castaways, translated by Frances M. López and introduced by Enrique Pupo-Walker, provides a reliable, student-friendly volume.  The Norton Critical edition, lvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, Chronicle of the Narváez Expedition (2013), edited by Ilan Stavans, includes related documents and critical essays. Morris Bishop’s biography, Odyssey of Cabeza de Vaca (1933), is in need of updating. Nicolás Echeverría adapted the castaway’s life for film, emphasizing the strangeness of native-white encounters, in Cabeza de Vaca (1991). Laila Lalami The Moor’s Account (2014) is the most recent novelistic retelling.

The Norton Critical edition, lvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, Chronicle of the Narváez Expedition (2013), edited by Ilan Stavans, includes related documents and critical essays. Morris Bishop’s biography, Odyssey of Cabeza de Vaca (1933), is in need of updating. Nicolás Echeverría adapted the castaway’s life for film, emphasizing the strangeness of native-white encounters, in Cabeza de Vaca (1991). Laila Lalami The Moor’s Account (2014) is the most recent novelistic retelling.

Cabeza de Vaca is commonly cited as a metacanonical figure, a placeholder or marker for broader trends in literary history. Gabriel García Márquez cites Cabeza de Vaca in a case for claiming Latin American identity apart from Spanish language and hegemony in “Fantasía y creación artistica en América Latina y el Caribe” (1998). Pupo-Walker emphasizes the sophisticated reordering of events in the Introduction to the 1993 translation Castaways, and like García Márquez, presents Cabeza de Vaca as central to the tradition of Hispanoamerican narrative. Ralph Bauer folds the account into a broader effort to decouple colonial literatures of the Americas from a United States that did not exist; Bauer has made the case repeatedly, most concisely in “Early American Literature and American Literary History at the ‘Hemispheric Turn'” (2010).

In Chicano studies, Cabeza de Vaca often appears as a figure of firstness. Echoing García Márquez, Juan Velasco puts the lost conquistador at the forefront of Chicano memoirists in “Automitografias: The Border Paradigm and Chicana/o Autobiography” (2004). In Reading and Writing the Latin American Landscape, Beatríz Rivera-Barnes situates dashed hopes against the God-like, regionally-defined hurakan (2009). Cassander L. Smith, in “Beyond the mediation, Cabeca de Vaca’s Relación and a Narrative of Negotiation” (2001), focuses on Esteban to note figures outside the text, not only in Cabeza de Vaca’s account, but in early American studies. Focusing on the Echeverría film, Luisela Alvary shows how Cabeza de Vaca’s story occasions a reconsideration of colonialism in “Imag(ni)ing Indigenous Spaces: Self and Other Converge in Latin America” (2004).

More narrowly, the Narváez expedition had marked regional or national pride. There is the timing of Buckingham Smith’s translation after the Mexican War and increasingly aggressive policies in the United States towards Latin America; in a speculative essay, “The Gulf of Mexico System and the ‘Latinness’ of New Orleans” (2006), Kirsten Silva Gruesz cites the gulf basin, limned by Cabeza de Vaca, as a border space between Spanish America and a commerce-driven United States. Turning manifest destiny to local history, a 1925 article by A.H. Phinney flagged the precise Narváez landing spot (with no regard for coastal morphology) at Johns Pass, in present-day St. Petersburg beach; see “Narvez and de Soto: Their Landing Places and the Town of Espirito Santo” (1925). Texas has its Cabeza de Vaca, while Floridians point to Indians mounds and claim him as their own.

The broader world of criticism follows several streams, with a pronounced disconnect due to language differences across disciplines. Colonial Latin Americanists letters read Cabeza de Vaca’s accounts against related narratives, and in the context of sixteenth-century transatlantic debates about the moral terms of conquest. José Rabasa discusses textual acts of violence in Writing Violence on the Northern Frontier: The Historiography of Sixteenth-Century New Mexico and the Legacy of Conquest (2000).

Adorno emphasizes crown reforms in Spain and pacification in “Peaceful Conquest and Law in the Relación [Account] of Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca” (1994). Beatriz Pastor Bodmer argues that diminished returns, or a discourse of failure, shaped the later sixteenth-century accounts such as Cabeza de Vaca’s in her influential study, The Armature of Conquest: Spanish Accounts of the Discovery of America, 1492-1589 (1995). Pablo García Loaeza examines therapeutic uses of writing with regards to Cabeza de Vaca and South America in “La conquista del Río de la Plata: Adverisdad, esperanza y escritura” (2011).

Attention to the literature of discovery boomed in the early 1990s due to the 500-year anniversary of Columbus’ voyage and the emergence of poststructuralist-postcolonial theory. Both shaped Cabeza de Vaca scholarship. Tzvetan Todorov’s classic The Conquest Of America: The Question of the Other (1992) examined semiotic exchange through an ethical lens. Stephen Greenblatt’s Marvelous Possessions: The Wonder of the New World (1992) deeply influenced the conversation, though without addressing Cabeza de Vaca specifically; one year earlier, in a special issue of the journal Representations edited by Greenblatt, Anthony Pagden would articulate the problem of establishing auctoritates, or the use of the self (or witness), to free direct experience from an enclosed hermeneutic loop; see his superlative study, “Ius et Factum: Text and Experience in the Writings of Bartolomé de Las Casas.” Carmen Moreno-Nuño treats the role of language in the Spanish conquest in “Cabeza de Vaca’s Relación in Light of Deleuze and Guattari’s Semiotics and Theory of Language” (1997). Anticipating arguments of the 1990s, Sylvia Molloy’s “Alteridad y reconicimiento en Los Naufragios de Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca” (1986) skillfully positions the narrator of the Relación between an imperial audience and an American space of alterity.

Given the protean qualities of a text that seems to draw from many genres, and its rhetorical dislocation as it speaks from the Americas to readers in Spain), much of the criticism struggles with where to place Cabeza de Vaca. Juan Bruce-Novoa notes the confusion of names, at the heart of Chicano identity, describing the figure he calls “ANCdV” as a castaway in tidal signifiers; see his “Shipwrecked in the Seas of Signification: Cabeza de Vaca’s Relación and Chicano Literature” (1993). Bauer describes Cabeza de Vaca from within a conflict of epistemes and ideas of empire in The Cultural Geography of Colonial American Literatures: Empire, Travel, Modernity (2003). Alan J. Silva draws heavily from Homi Bhabha to emphasize Cabeza de Vaca’s negotiations from within a “middle spaces” in “Conquest, Conversion, and the Hybrid Self in Cabeza de Vaca’s Relación” (1999); Silvia Spitta portrays him as an early figure of “transculturation” (again, the firstness), as one negotiating between shamanistic practices and Christian discourse, in Between Two Waters: Narratives of Transculturation in Latin America (1995). Steven P. Liparulo notes semantic instability in “‘From Fear to Wisdom’: Augustinian Semiotics and Self-Fashioning in Cabeza de Vaca’s Relación” (2006). Through deep and wide reading of interwoven accounts, Rolena Adorno shows how Cabeza de Vaca’s vulnerability led to complex representations of the relations between different groups in “The Negotiation of Fear in Cabeza de Vaca’s Naufragios” (1991). Maureen Ahern pulls together theoretical terms and the prevailing interest amongst historians at the time in a frontier “go-between” to show (like Adorno) how Cabeza de Vaca mediated signs of verbal and religious order in “The Cross and the Gourd: The Appropriation of Ritual Signs in the Relaciones of Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca and Fray Marcos de Niza” (1993).

The more even-handed readings remain open to discursive complexity, the variety of forms packed into one account, even as they draw out the narrative strains that fed into Cabeza de Vaca’s hybrid account. Edgardo Rivera Martinez takes issue with readings of a creole author and sees the account as a complex mélange in “Singularidad y carácter de los Naufragios de Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca” (1993). Unwilling to perpetuate what he sees as a hagiographic strain in the criticism, Juan Francisco Maura argues for reading Cabeza de Vaca for strategic purpose and rhetorical design in “Veracidad en los Naufragios: La técnica narrativa de Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca” (1995). Alberto Prieto Calixto emphasizes captivity, a theme that cut across genres and geographic boundaries, in a reading that sets the narrative between worlds, in Héroes, Prisioneros y Renegados: El Cautiverio en la Narrativa Hispana de los Siglos XVI y XVII (2008). Enrique Pupo-Walker notes the difficulty of pinning down an evasive, hybrid text, and following a compelling review of the criticism to date, emphasizes the uses of hagiography in “Pesquisas para una nueva lectura de los Naufragios de Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca” (1995). Kun Jong Lee highlights biblical themes, particularly Paul’s epiphany on the road to Damascus, in “Pauline Typology in Cabeza de Vaca’s Naufragios” (1999). Claret Vargas, with a nod to Bodmer Pastor and attention to both war manuals from the Moorish wars and conquest of America, shows how the discourse of failure was mobilized to suggest strategies for future success in “‘De Muchas y Muy Bárbaras Naciones con Quien Conversé y Viví’: Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca’s Naufragios as a War Tactics Manual” (2007). Lucía Invernizzi Santa Cruz argues convincingly in “Naufragios e Infortunios: Discurso que transforma fracasos en triumfos” (1987) how military failures opened the narrative space for triumphs of the spirit, a proper occupation, and therefore reward for service to the King. Nan Goodman makes an equally convincing case that, as treasurer to the Narváez expedition, Cabeza de Vaca drew from mercantilist theory in “Mercantilism and Cultural Difference in Cabeza de Vaca’s Relación” (2005).

The scholarship is unusually rich. ANCdV’s variously-titled work holds equal value to archaeologists, historians of the Gulf South and Latin Americanists; to historians of empire and native Americans; and to students of colonial Latin America literature as well as what would become (ahistorically) the United States. Conclusions about his legacy often follow separate streams of scholarship, and at this point, the most important contribution would be a single volume that synthesizes the interpretations into one volume, pulling together the range of perspectives that he continues to represent. Such a book would soon find its place on library shelves. What did I miss or misrepresent? Contact me.

Further Reading

Adorno, Rolena. “Cómo leer Mala Cosa: mitos caballerescos y amerindios en los Naufragios de Cabeza de Vaca.” In Beatriz González Stephan and Lúcia Helena Costigan, eds. Critica y descolonización: el sujeto colonial en la cultura latinoamericana. Caracas: Universidad Central de Venezuela, 1992, 89-107.

“The Negotiation of Fear in Cabeza de Vaca’s Naufragios.” Representations 33 (1991): 163-199.

_________ . “Peaceful Conquest and Law in the Relación [Account] of Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca.” In Francisco Javier Cevallos-Candau, Jeffrey A. Cole, Nina M. Scott, and Nicomedes Suárez, eds. Coded Encounters: Writing, Gender, and Ethnicity in Colonial Latin America. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1994, 75-86.

Ahern, Maureen. “The Cross and the Gourd: The Appropriation of Ritual Signs in the Relaciones of Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca and Fray Marcos de Niza.” In Jerry M. Williams and Robert E. Lewis, eds. Early Images of the Americas: Transfer and Invention. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1993. 215-44.

Alvaray, Luisela. “Imag(ni)ing Indigenous Spaces: Self and Other Converge in Latin America.” Film and History: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television Studies 34, no. 2 (2004): 58-64.

Barrera, Trinidad. “Introducción.” In Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, Naufragios. Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 1985.

Bauer, Ralph. The Cultural Geography of Colonial American Literatures: Empire, Travel, Modernity. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

_________ . “Early American Literature and American Literary History at the ‘Hemispheric Turn.’” Early American Literature 45, no. 2 (2010): 217-33.

Bishop, Morris. Odyssey of Cabeza de Vaca. New York: Century, 1933.

Bruce-Novoa, Juan. “Shipwrecked in the Seas of Signification: Cabeza de Vaca’s Relación and Chicano Literature.” In Maria Herrera-Sobek, ed. Reconstructing a Chicano/a Literary Heritage: Hispanic Colonial Literature of the Southwest. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1993, 3–23.

Cabeza de Vaca, Álvar Nuñez. His Account, His Life and the Expedition of Pánfilo de Narváez. Edited by Rolena Adorno and Patrick Charles Pautz. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999.

__________ . The Account: Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca’s Relación. Translated by Martín A. Favata and José B. Fernández. Houston: Arte Público Press, 1993.

__________ . Chronicle of the Narváez Expedition. Edited by Ilan Stavans. New York: Norton, 2013.

__________ . Castaways. Translated by Frances M. López-Morillas. Ed. Enrique Pupo-Walker. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

__________ . The Narrative of Cabeza de Vaca. Edited and Translated by Rolena Adorno and Patrick Charles Pautz. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1999.

Carreño, Antonio. “Naufragios de Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca: una retórica de de la crónica colonial.” Revista Iberoamericana 53, no. 140 (1987): 499-516.

Dowling, Lee W. “Story vs. Discourse in the Chronicle of the Indies: Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca’s Relación.” Hispanic Journal 5, no. 2 (1984): 89-99.

Ferro, Donatella. “Oviedo/Cabeza de Vaca: Debito Testuale e ‘tarea de acumulación y corrección.’” In G. B. Di Cesare, ed. El Girador: studi di letteratura iberiche e ibero-americane offerti a Giuseppe Bellini. Rome: Bulzoni, 1993, 425-35.

García Márquez, Gabriel. “Fantasía y creación artistica en América Latina y el Caribe.” Voces. Arte y literatura 2 (March 1998).

Garcia Loaeza, Pablo. “La Conquista del Río de la Plata: Adversidad, esperanza y escritura.” Hispania 94, no. 4 (Dec. 2011): 603-14.

Goodman, Nan. “Mercantilism and Cultural Difference in Cabeza de Vaca’s Relacion.” Early American Literature 40, no. 2 (2005): 229-50.

Invernizzi, Santa Cruz Lucía. “Naufragios e Infortunios: discurso que transforma fracaso en triunfos.” Disposito 28-29 (1986): 99-111.

Lagmanovich, David. “Los Naufragios de Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca como construcción narrativa.” Kentucky Romance Quarterly 25, no. 1 (1978): 23-28.

Lalami, Laila. The Moor’s Account: A Novel. New York: Pantheon: New York, 2014.

Lastra, Pedro. “Espacios de Álvar Núñez: las transformaciones de una escritura.” Cuadernos Americanos 3 (1984): 150-164.

Lee, Kun Jong. “Pauline Typology in Cabeza de Vaca’s Naufragios.” Early American Literature 34, no. 3 (1999): 241-62.

Lewis, Robert E. “Los Nafragios de Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca: historia y ficción.” Revista Ibericanamerica 48, no. 120-121 (1982): 681-94.

Liparulo, Steven P. “‘From Fear to Wisdom’: Augustinian Semiotics and Self-Fashioning in Cabeza de Vaca’s Relación.” Arizona Quarterly 62, no. 2 (Summer 2006): 1-25.

Maura, Francisco. “Veracidad en los Naufragios: La técnica narrativa de Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca.” Revista Iberoamericana 61, no. 170-71 (1995): 187-95.

Mignolo, Walter. “Canon and Corpus: An Alternate View of Comparative Literary Studies in Colonial Situations.” Dedalus 1 (1991): 219-44.

Molloy, Silvia. “Alteridad y reconicimiento en Los Naufragios de Alvar Núñez Caeza de Vaca.” In Alfred Lozada, ed. Selected Proceedings of the Seventh Louisiana Conference on Hispanic Languages and Literatures. Baton Rouge: Louisiana S U P, 1986, 13-33. Also in Nueva Revista de Filología Hispánica 35, no. 2 (1987): 425-49.

Moreno-Nuño, Carmen. “Cabeza de Vaca’s Relación in Light of Deleuze and Guattari’s Semiotics and Theory of Language.” Romance Languages Annual 8 (1997): 589-96.

Oviedo y Valdéz, Gonzalo Fernández. [“The Expedition of Pánfilo de Narváez,” 15:1-7]. General and Natural History of the Indies [1535]. Edited by Jose Amador de los Rios. Madrid, 1851-55.

Oviedo y Valdéz, Gonzalo Fernández and Harbert Davenport. “The Expedition of Pánfilo de Narváez.” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly 27, no. 3 (Jan. 1924): 217-41.

Pagden, Anthony. “Ius et Factum: Text and Experience in the Writings of Bartolomé de Las Casas.” Representations 33 (Winter 1991): 147-62. Reprinted in Stephen Greenblatt, ed. New World Encounters. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993, 85-100.

Pastor, Beatriz. The Armature of Conquest: Spanish Accounts of the Discovery of America, 1492-1589. Translated by Lydia Longstreth Hunt. Stanford: Stanford University of California Press, 1992.

Phinney, A.H. “Narváez and De Soto: Their Landing Places and the Town of Espíritu Santo.” Florida Historical Quarterly 3, no. 3 (1925): 15-21.

Prieto Calixto, Alberto. Héroes, Prisioneros y Renegados: El Cautiverio en la Narrativa Híspanica de los Siglos XVI y XVII. Gijón: Prensa Académica Castellana, 2008.

Pupo-Walker, Enrique. “Pesquisas para una nueva lectura de los Naufragios de Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca.” Revista iberoamericana 53, no. 140 (1987): 519-35.

Rabasa, José. “De la alegoresis etnográfica en los Naufragios de Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca.” Revista Iberoamericana 61, no. 170-171 (1995): 175-185.

_________ . Writing Violence on the Northern Frontier: The Historiography of Sixteenth Century New Mexico and Florida and the Legacy of Conquest. Durham: Duke University Press, 2000.

Rivera-Barnes, Beatríz and Jerry Hoeg. Reading and Writing the Latin American Landscape. New York: Palgrave-Macmillan, 2009.

Rivera Martínez, Edgardo. “Singularidad y carácter de los Naufragios de Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca.” Revista de crítica literaria hispanoamericana 19, no. 38 (1993): 301-315.

Silva, Alan J. “Conquest, Conversion, and the Hybrid Self in Cabeza de Vaca’s Relación.” Post Identity 4, no. 1 (1999).

Smith, Cassander L. “Beyond the Mediation: Esteban, Cabeza de Vaca’s Relación and a Narrative Negotiation.” Early American Literature 47, no. 2 (2001): 267-91.

Spitta, Sylvia. Between Two Waters: Narratives of Transculturation in Latin America. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 1995.

__________ . “Chamanismo y cristiandad: una lectura de la lógica intercultural de los Naufragios de Cabeza de Vaca.” Revista de crítica literaria latinoamericana 19, no. 38 (1993): 317-30.

Todorov, Tzvetan. The Conquest Of America: The Question Of The Other. Transl. Richard Howard. New York: HarperPerennial, 1992.

Urdapilleta, Antonio. Adanzas y Desventuras de Álvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca. Madrid: Gráficas, 1949.

Vargas, Claret. “De Muchas y Muy Bárbaras Naciones con Quien Conversé y Viví”: Alvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca’s Naufragios as a War Tactics Manual.” Hispanic Review 75, no. 1 (Winter 2007): 1-22.

Wade, Mariah. “Go-Between: the Roles of Native American Women and Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca in Southern Texas in the 16th Century.” Journal of American Folklore 112, no.445 (1990): 332-42.