What does travel teach us about literature? How can literature help us understand a place? A Road Course in Early American Literature explores these questions through personal narrative and traditional scholarship. Journeying with familiar and lesser-known works, I explain my passion for the American survey to 1860, a college course I have taught for two decades. These pages are part travelogue, part resource guide, and I hope, challenging fun. (For the scholarship see the book’s Footnote Trails.) Join me, as I explore America’s back roads and storied past through the perspective of a teacher, scholar, unrepentant tourist, father, friend and son. Purchase your copy from a local bookstore or the University of Alabama Press.

Philadelphia–Franklin’s Walk

On October 6, 1723 a young runaway named Benjamin Franklin walked down a Delaware River wharf, stepped onto dry land, and for the first time his life, trod the streets of Philadelphia. His circuit that morning would become the iconic passage in a story of his life–the book we now call the Autobiography. Franklin buys “three great puffy rolls” and makes short loop through today’s Center City, one loaf of puffy bread tucked under each arm. Years later he described that fateful day, and while the image has hardened into reality, his original manuscript shows how the passage was carefully revised. Here’s the original, from a genetic (or literal) transcript, edited by Franklin scholars J.A. Leo Lemay and P.M. Zall:

Thus I went up Market Street as far as fourth Street, passing by the Door of Mr. Read, afterwards my future Wife’s Father, when she standing at the Door saw me, & thought I made as I certainly did a most awkward ridiculous Appearance. Then I turn’d and went down Chestnut Street and part of Walnut Street, eating my Roll all the way, and drinking coming round found my self again at Market street Wharff, near the boat I came in, to which I went for a Draught of the River Water, and being fill’d with one of my Rolls, gave the other two to a Woman & her Child that came down the River in the Boat with us and were waiting to go farther.

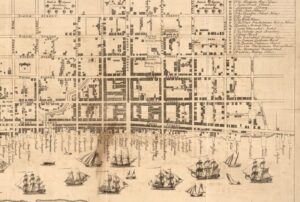

The immediacy makes this passage so convincing. Anyone familiar with Philadelphia can reconstruct the route. Franklin heads West, down the main drag of Market Street, and crosses First, Second, and Third Streets; he turns another left, onto Fourth, and crosses the tree streets, before looping back to the Delaware River.

The spatial prompts the temporal. The grid encapsulates a life. When I review this passage with students, I pull up maps of London and Philadelphia. The contrast allows them to visualize the Old Country and the blank space of an American life. Franklin’s friend Nicholas Scull drew the Philadelphia map in 1762; Scull was also a member of Franklin’s famed “Junto,” and a few decades earlier, witness to the Walking Purchase. The clarity of the squared corners on the 1762 map environ a rebirth–an American plot too easily told. Projecting his life onto the grid, Franklin makes subtle changes that sharpen the drama and tease out the temporal reach. The insertion, “as I certainly did,” nods to a futurity that did not exist in 1723. Young Ben first sees his in-laws at Fourth and Market, even though any relationship with Deborah Reed remained years away. Early humility anticipates later success; generous even as a hungry teenager, apparently, Franklin donates his uneaten puffy roll. The autobiography presumes to be a private affair, addressed later to his son William Templeton and peppered with seemingly idle banter. Yet the revisions show a more tightly-spooled account. Don’t be fooled. Even the most casual moments in any pattern life are carefully composed–the easy flow that follows many crossouts, insertions, deletions, and revision.

The spatial prompts the temporal. The grid encapsulates a life. When I review this passage with students, I pull up maps of London and Philadelphia. The contrast allows them to visualize the Old Country and the blank space of an American life. Franklin’s friend Nicholas Scull drew the Philadelphia map in 1762; Scull was also a member of Franklin’s famed “Junto,” and a few decades earlier, witness to the Walking Purchase. The clarity of the squared corners on the 1762 map environ a rebirth–an American plot too easily told. Projecting his life onto the grid, Franklin makes subtle changes that sharpen the drama and tease out the temporal reach. The insertion, “as I certainly did,” nods to a futurity that did not exist in 1723. Young Ben first sees his in-laws at Fourth and Market, even though any relationship with Deborah Reed remained years away. Early humility anticipates later success; generous even as a hungry teenager, apparently, Franklin donates his uneaten puffy roll. The autobiography presumes to be a private affair, addressed later to his son William Templeton and peppered with seemingly idle banter. Yet the revisions show a more tightly-spooled account. Don’t be fooled. Even the most casual moments in any pattern life are carefully composed–the easy flow that follows many crossouts, insertions, deletions, and revision.

That leaves us a question for us today. What slimmed-down story, composed in retrospect, do we tell about our own younger years?

Want to read more? Check out A Road Course in Early American Literature: Travel and Teaching from Atzlán to Amherst.